A New Post

Probability and the Art of Modeling Uncertainty

PROBABILITY AND THE ART OF MODELING UNCERTAINTY (COURSE NOTES)

Since probability effectively corresponds to a fraction, it is a value between 0 and 1. Of course, we can have impossible events that have probability 0, or events that deterministically happen and thus have probability 1. Each time we model uncertainty in the world, there will be some underlying experiment (such as flipping a coin in our running example). An event happens with probability q∈[0,1] if in a massive number of repeats of the experiment, the event happens roughly a fraction q of the time; more repeats of the experiment make it so that the fraction gets closer to q.

Some times, an underlying experiment cannot possibly be repeated. Take for instance weather forecasting. Whereas we could actually physically flip a coin many times to repeat the same experiment, we cannot physically repeat a real-life experiment for what different realizations of tomorrow’s weather will be. We could wait until tomorrow to see the weather, but then we would need a time machine to go back in time by one day to repeat and see what the weather is like tomorrow (and this assumes that there’s some inherent randomness in tomorrow’s weather)! In such a case, our only hope is to somehow model or simulate tomorrow’s weather given measurements up to present time.

A good model

Different people could model the same real world problem differently! Throughout the course, a recurring challenge in building computer programs that reason probabilistically is figuring out how to model real-world problems. A good model — even if not actually accurate in describing, for instance, the science behind weather — enables us to make good predictions.

Once a weather forecaster has anchored some way of modeling or simulating weather, then if it claims that there’s a 30% chance of rain tomorrow, we could interpret this as saying that using their way of simulating tomorrow’s weather, in roughly 30% of simulated results for tomorrow’s weather, there is rain.

A probability is a number that is at least 0 and at most 1.

There is only one way to model tomorrow’s weather. False: Different people can model weather differently, leading to different forecasts.

Let’s say I have a coin that, when tossed, is heads with probability 0.7. Select all the statements below which are true.

If we flip the coin 10 times, it is possible that none of them are heads. As we increase the number of times we flip the coin, the fraction of coin flips that are heads becomes closer to 0.7.

If we flip the coin 10 times, it is indeed possible that none of them are heads. In fact, even if we flip the coin 1,000,000 times, it is still possible that none of them are heads albeit such an outcome is extremely unlikely (by the end of this first section of the course, you’ll be able to calculuate just how unlikely). In particular, it does not have to be the case that with 1,000 flips, there will be exactly 700 heads, or that even with 1,000,000 flips, there will be exactly 700,000 heads. However, as we increase the number of flips, the fraction of coin flips that are heads will indeed become closer to 0.7.

TWO INGREDIENTS TO MODELING UNCERTAINTY (COURSE NOTES)

When we think of an uncertain world, we will always think of there being some underlying experiment of interest. To model this uncertain world, it suffices to keep track of two things:

The set of all possible outcomes for the experiment: this set is called the sample space and is usually denoted by the Greek letter Omega Ω. (For the fair coin flip, there are exactly two possible outcomes: heads, tails. Thus, Ω={heads,tails}.)

The probability of each outcome: for each possible outcome, assign a probability that is at least 0 and at most 1. (For the fair coin flip, P(heads)=12 and P(tails)=12.)

Notation: Throughout this course, for any statement S, “P(S)” denotes the probability of S happening.

In Python:

model = {‘heads’: 1/2, ‘tails’: 1/2} In particular, we see that we can model uncertainty in code using a Python dictionary. The sample space is precisely the keys in the dictionary:

sample_space = set(model.keys()) {‘tails’, ‘heads’} Of course, the dictionary gives us the assignment of probabilities, meaning that for each outcome in the sample space (i.e., for each key in the dictionary), we have an assigned probability:

model[‘heads’] 0.5 model[‘tails’] 0.5 A few important remarks:

-

The sample space is always specified to be collectively exhaustive, meaning that every possible outcome is in it, and mutually exclusive, meaning that once the experiment is run (e.g., flipping the fair coin), exactly one possible outcome in the sample space happens. It’s impossible for multiple outcomes in the sample space to simultaneously happen! It’s also impossible for none of the outcomes to happen!

-

Probabilities can be thought of as fractions of times outcomes occur; thus, probabilities are nonnegative and at least 0 and at most 1.

-

If we add up the probabilities of all the possible outcomes in the sample space, we get 1. (For the fair coin flip, P(heads)+P(tails)=12+12=1.)

Some intuition for this: Consider the coin flipping experiment. What does the fraction of times heads occur and the fraction of times tails occur add up to? Since these are the only two possible outcomes (and again, recall that these outcomes are exclusive in that they can’t simultaneously occur, and exhaustive since they are the only possible outcomes), these two fractions will always sum to 1. For a massive number of repeats of the experiment, these two fractions correspond to P(heads) and P(tails); the fractions sum to 1 and so these probabilities also sum to 1.

Recall that for each key in a Python dictionary, there is an associated value. A Python dictionary stores a valid probability distribution when the values are each at least 0 and at most 1; moreover, when we add up the values for all the keys, the sum is equal to 1.

How a sample space is chosen is not unique. As a more involved example, we could even have a sample space that consists of two fair six-sided dice being thrown, where we basically discard all the information about the second die’s outcome to reason about the first die. We could also add junk outcomes that are assigned probability 0. However, in general, it’s best to keep the sample space as simple as possible to solve the problem at hand.

Suppose we use the sample space {1,2,3,4,5,6}. Write the Python dictionary that encodes a valid probabilistic model for the fair die roll experiment using this sample space. (Your answer should be the Python dictionary itself, and not the dictionary assigned to a variable, so please do not include, for instance “model =” before specifying your answer. Also please be accurate with your fractions up to 5 decimals.)

Assign each outcome probability 1/6: {1: 1/6, 2: 1/6, 3: 1/6, 4: 1/6, 5: 1/6, 6: 1/6}

PROBABILITY SPACES (COURSE NOTES)

At this point, we’ve actually already seen the most basic data structure used throughout this course for modeling uncertainty, called a finite probability space (in this course, we’ll often also just call this either a probability space or a probability model):

A finite probability space consists of two ingredients:

-

a sample space Ω consisting of a finite (i.e., not infinite) number of collectively exhaustive and mutually exclusive possible outcomes

-

an assignment of probabilities: for each possible outcome ω∈Ω, we assign a probability P(outcome ω) at least 0 and at most 1, where we require that the probabilities across all the possible outcomes in the sample space add up to 1:

∑ω∈ΩP(outcome ω)=1.

Notation: As shorthand we occasionally use the tuple “(Ω,P)” to refer to a finite probability space to remind ourselves of the two ingredients needed, sample space Ω and an assignment of probabilities P. As we already saw, in code these two pieces can be represented together in a single Python dictionary. However, when we want to reason about probability spaces in terms of the mathematics, it’s helpful to have names for the two pieces.

Why finite? Of the two pieces making up a finite probability space (Ω,P), the sample space Ω being finite is a fairly natural constraint, corresponding to how we typically work with Python dictionaries where there is only a finite number of keys. As we’ll see, finite probability spaces are already extremely useful in practice. Pedagogically, finite probability spaces also provide a great intro to probability theory as they already carry a wealth of intuition, much of which carries over to a more complete story of general probability spaces!

TABLE REPRESENTATION (COURSE NOTES)

A probability space is a data structure in that we can always visualize as a table of nonnegative entries that sum to 1. Let’s see a concrete example of this, first writing the table out on paper and then coding it up.

Example: Suppose we have a model of tomorrow’s weather given as follows: sunny with probability 1/2, rainy with probability 1/6, and snowy with probability 1/3. Here’s the probability space, shown as a table:

Probability sunny 1/2Outcome rainy 1/6

snowy 1/3 Note: This a table of 3 nonnegative entries that sum to 1. The rows correspond to the sample space Ω={sunny,rainy,snowy}.

We will often use this table representation of a probability space to tell you how we’re modeling uncertainty for a particular problem. It provides the simplest of visualizations of a probability space.

Of course, in Python code, the above probability space is given by:

prob_space = {‘sunny’: 1/2, ‘rainy’: 1/6, ‘snowy’: 1/3} A different way to code up the same probability space is to separately specify the outcomes (i.e., the sample space) and the probabilities:

outcomes = [‘sunny’, ‘rainy’, ‘snowy’] probabilities = np.array([1/2, 1/6, 1/3]) The i-th entry of outcomes has probability given by the i-th entry of probabilities. Note that probabilities is a vector of numbers that we represent as a Numpy array. Numpy has various built-in methods that enable us to easily work with vectors (and more generally arrays) of numbers.

ADDENDUM: MORE ON SAMPLE SPACES

In the video, we saw that a sample space encoding the outcomes of 2 coin flips encodes all the information for 1 coin flip as well. Thus, we could use the same sample space to model a single coin flip. However, if we really only cared about a single coin flip, then a sample space encoding 2 coin flips is richer than we actually need it to be!

When we model some uncertain situation, how we specify a sample space is not unique. We saw an example of this already in an earlier exercise where for rolling a single six-sided die, we can choose to name the outcomes differently, saying for instance “roll 1” instead of “1”. We could even add a bunch of extraneous outcomes that all have probability 0. We could add extraneous information that doesn’t matter such as “Alice rolls 1”, “Bob rolls 1”, etc where we enumerate out all the people who could roll the die in which the outcome is a 1. Sure, depending on the problem we are trying to solve, maybe knowing who rolled the die is important, but if we don’t care about who rolled the die, then the information isn’t helpful but it’s still possible to include this information in the sample space.

Generally speaking it’s best to choose a sample space that is as simple as possible for modeling what we care about solving. For example, if we were rolling a six-sided die, and we actually only care about whether the face shows up at least 4 or not, then it’s sufficient to just keep track of two outcomes, “at least 4” and “less than 4”.

Event

Subset of sample space

ADDENDUM: CODE FOR DEALING WITH SETS IN PYTHON

In the video, the set operations can actually be implemented in Python as follows:

sample_space = {‘HH’, ‘HT’, ‘TH’, ‘TT’} A = {‘HT’, ‘TT’} B = {‘HH’, ‘HT’, ‘TH’} C = {‘HH’} A_intersect_B = A.intersection(B) # equivalent to “B.intersection(A)” or “A & B” A_union_C = A.union(C) # equivalent to “C.union(A)” and also “A | C” B_complement = sample_space.difference(B) # equivalent also to “sample_space - B”

ADDENDUM: PROBABILITIES WITH EVENTS AND CODE

From the videos, we see that an event is a subset of the sample space Ω. If you remember our table representation for a probability space, then an event could be thought of as a subset of the rows, and the probability of the event is just the sum of the probability values in those rows!

The probability of an event A⊆Ω is the sum of the probabilities of the possible outcomes in A:

P(A)≜∑ω∈A P(outcome ω),

where “≜” means “defined as”.

We can translate the above equation into Python code. In particular, we can compute the probability of an event encoded as a Python set event, where the probability space is encoded as a Python dictionary prob_space:

def prob_of_event(event, prob_space): total = 0 for outcome in event: total += prob_space[outcome] return total Here’s an example of how to use the above function:

prob_space = {‘sunny’: 1/2, ‘rainy’: 1/6, ‘snowy’: 1/3} rainy_or_snowy_event = {‘rainy’, ‘snowy’} print(prob_of_event(rainy_or_snowy_event, prob_space))

| In general, suppose that a probability space has m (not infinite) different possible outcomes, i.e., the sample space Ω has size | Ω | =m. How many events are there, in terms of m? |

There are 2^m possibilities. To count the number of events, note that to form each event, we go through each of the m possible outcomes and we either include the outcome or not. Thus, the total number of possible events is:

2 (whether we include the first outcome or not) multiplied by 2 (whether we include the second outcome or not) multiplied by … finally multiplied by 2 (whether we include the m-th outcome or not) = 2m.

A FIRST LOOK AT “RANDOM VARIABLES”

Follow along in an IPython prompt.

We continue with our weather example.

prob_space = {‘sunny’: 1/2, ‘rainy’: 1/6, ‘snowy’: 1/3}

We can simulate tomorrow’s weather using the above model of the world. Let’s simulate two different values, one (which we’ll call W for “weather”) for whether tomorrow will be sunny, rainy, or snowy, and another (which we’ll call I for “indicator”) that is 1 if it is sunny and 0 otherwise:

random_outcome = comp_prob_inference.sample_from_finite_probability_space(prob_space) W = random_outcome if random_outcome == ‘sunny’: I = 1 else: I = 0

Print out the variables W or I to see that they take on specific values. Then re-run the above block of code a few times.

You should see that W and I change and are random (following the probabilities given by the probability space).

This code shows something that’s of key importance that we’ll see throughout the course. Variables W and I store the values of what are called random variables.

RANDOM VARIABLES (COURSE NOTES)

To mathematically reason about a random variable, we need to somehow keep track of the full range of possibilities for what the random variable’s value could be, and how probable different instantiations of the random variable are. The resulting formalism may at first seem a bit odd but as we progress through the course, it will become more apparent how this formalism helps us study real-world problems and address these problems with powerful solutions.

To build up to the formalism, first note, computationally, what happened in the code in the previous part.

First, there is an underlying probability space (Ω,P), where Ω={sunny,rainy,snowy}, and

P(sunny)=1/2,P(rainy)=1/6,P(snowy)=1/3. A random outcome ω∈Ω is sampled using the probabilities given by the probability space (Ω,P). This step corresponds to an underlying experiment happening.

Two random variables are generated:

W is set to be equal to ω. As an equation:

W(ω)=ωfor ω∈{sunny,rainy,snowy}. This step perhaps seems entirely unnecessary, as you might wonder “Why not just call the random outcome W instead of ω?” Indeed, this step isn’t actually necessary for this particular example, but the formalism for random variables has this step to deal with what happens when we encounter a random variable like I.

I is set to 1 if ω=sunny, and 0 otherwise. As an equation:

I(ω)={1if ω=sunny,0if ω∈{rainy,snowy}. Importantly, multiple possible outcomes (rainy or snowy) get mapped to the same value 0 that I can take on.

We see that random variable W maps the sample space Ω={sunny,rainy,snowy} to the same set {sunny,rainy,snowy}. Meanwhile, random variable I maps the sample space Ω={sunny,rainy,snowy} to the set {0,1}.

In general:

Definition of a “finite random variable” (in this course, we will just call this a “random variable”): Given a finite probability space (Ω,P), a finite random variable X is a mapping from the sample space Ω to a set of values X that random variable X can take on. (We will often call X the “alphabet” of random variable X.)

For example, random variable W takes on values in the alphabet {sunny,rainy,snowy}, and random variable I takes on values in the alphabet {0,1}.

Quick summary: There’s an underlying experiment corresponding to probability space (Ω,P). Once the experiment is run, let ω∈Ω denote the outcome of the experiment. Then the random variable takes on the specific value of X(ω)∈X.

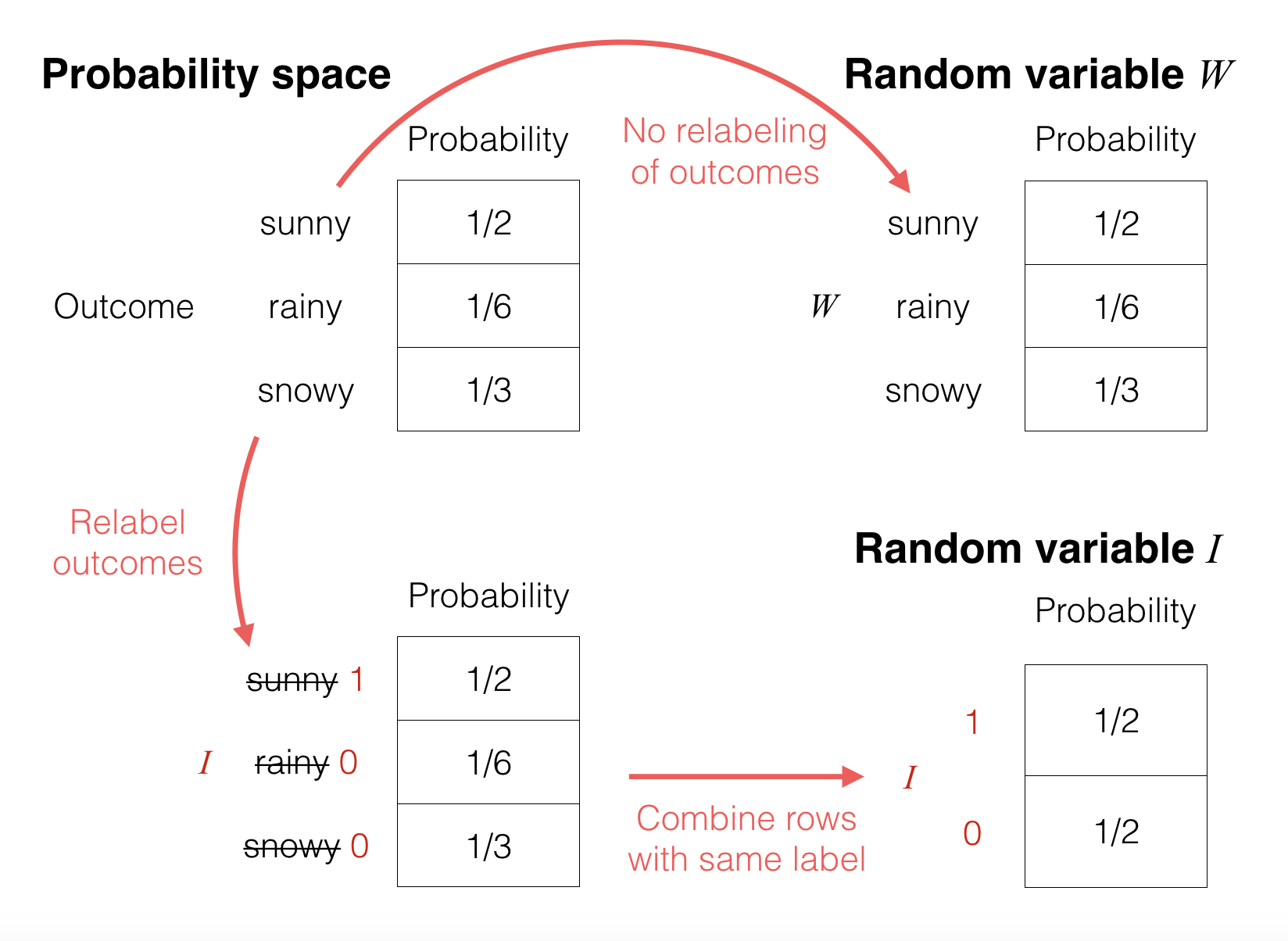

Explanation using a picture: Continuing with the weather example, we can pictorially see what’s going on by looking at the probability tables for: the original probability space, the random variable W, and the random variable I:

These tables make it clear that a “random variable” really is just reassigning/relabeling what the values are for the possible outcomes in the underlying probability space (given by the top left table):

-

In the top right table, random variable W does not do any sort of relabeling so its probability table looks the same as that of the underlying probability space.

-

In the bottom left table, the random variable Irelabels/reassigns “sunny” to 1, and both “rainy” and “snowy” to 0. Intuitively, since two of the rows now have the same label 0, it makes sense to just combine these two rows, adding their probabilities (16+13=12). This results in the bottom right table.

Technical note: Even though the formal definition of a finite random variable doesn’t actually make use of the probability assignment P, the probability assignment will become essential as soon as we talk about how probability works with random variables.

RANDOM VARIABLES NOTATION AND TERMINOLOGY (COURSE NOTES)

In this course, we denote random variables with capital/uppercase letters, such as X, W, I, etc. We use the phrases “probability table”, “probability mass function” (abbreviated as PMF), and “probability distribution” (often simply called a distribution) to mean the same thing, and in particular we denote the probability table for X to be pX or pX(⋅).

We write pX(x) to denote the entry of the probability table that has label x∈X where X is the set of values that random variable X takes on. Note that we use lowercase letters like x to denote variables storing nonrandom values. We can also look up values in a probability table using specific outcomes, e.g., from earlier, we have pW(rainy)=1/6 and pI(1)=1/2.

Note that we use the same notation as in math where a function f might also be written as f(⋅) to explicitly indicate that it is the function of one variable. Both f and f(⋅) refer to a function whereas f(x) refers to the value of the function f evaluated at the point x.

As an example of how to use all this notation, recall that a probability table consists of nonnegative entries that add up to 1. In fact, each of the entries is at most 1 (otherwise the numbers would add to more than 1). For a random variable X taking on values in X, we can write out these constraints as:

0≤pX(x)≤1for all x∈X,∑x∈XpX(x)=1.

Often in the course, if we are making statements about all possible outcomes of X, we will omit writing out thealphabet X explicitly. For example, instead of the above, we might write the following equivalent statement:

0≤pX(x)≤1for all x,∑xpX(x)=1.

U and V have the same PMF but they are associated with different probability spaces.

In general, for a real-valued function g (i.e., it maps real numbers to real numbers), is g(f(W)) a random variable?

Yes: g just relabels the outcome labels of the probability table for f(W).

RELATING TWO RANDOM VARIABLES (COURSE NOTES)

At the most basic level, inference refers to using an observation to reason about some unknown quantity. In this course, the observation and the unknown quantity are represented by random variables. The main modeling question is: How do these random variables relate?

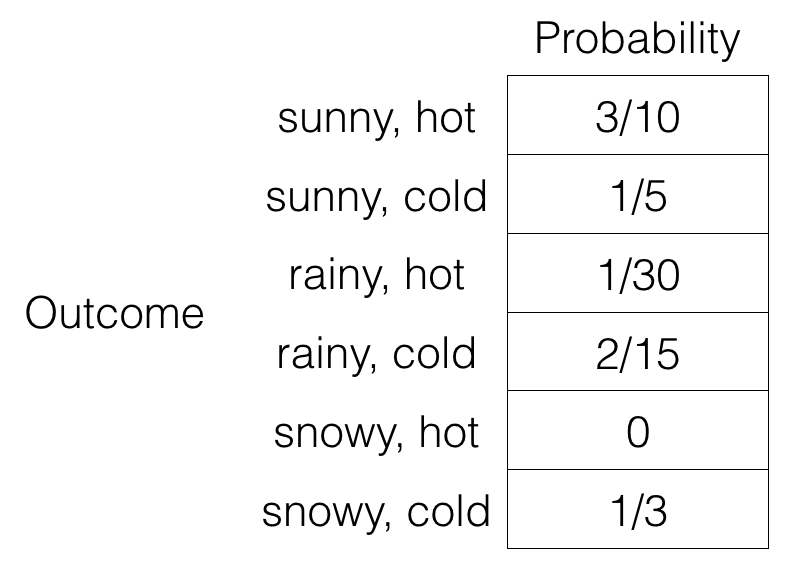

Let’s build on our earlier weather example, where now another outcome of interest appears, the temperature, which we quantize into to possible values “hot” and “cold”. Let’s suppose that we have the following probability space:

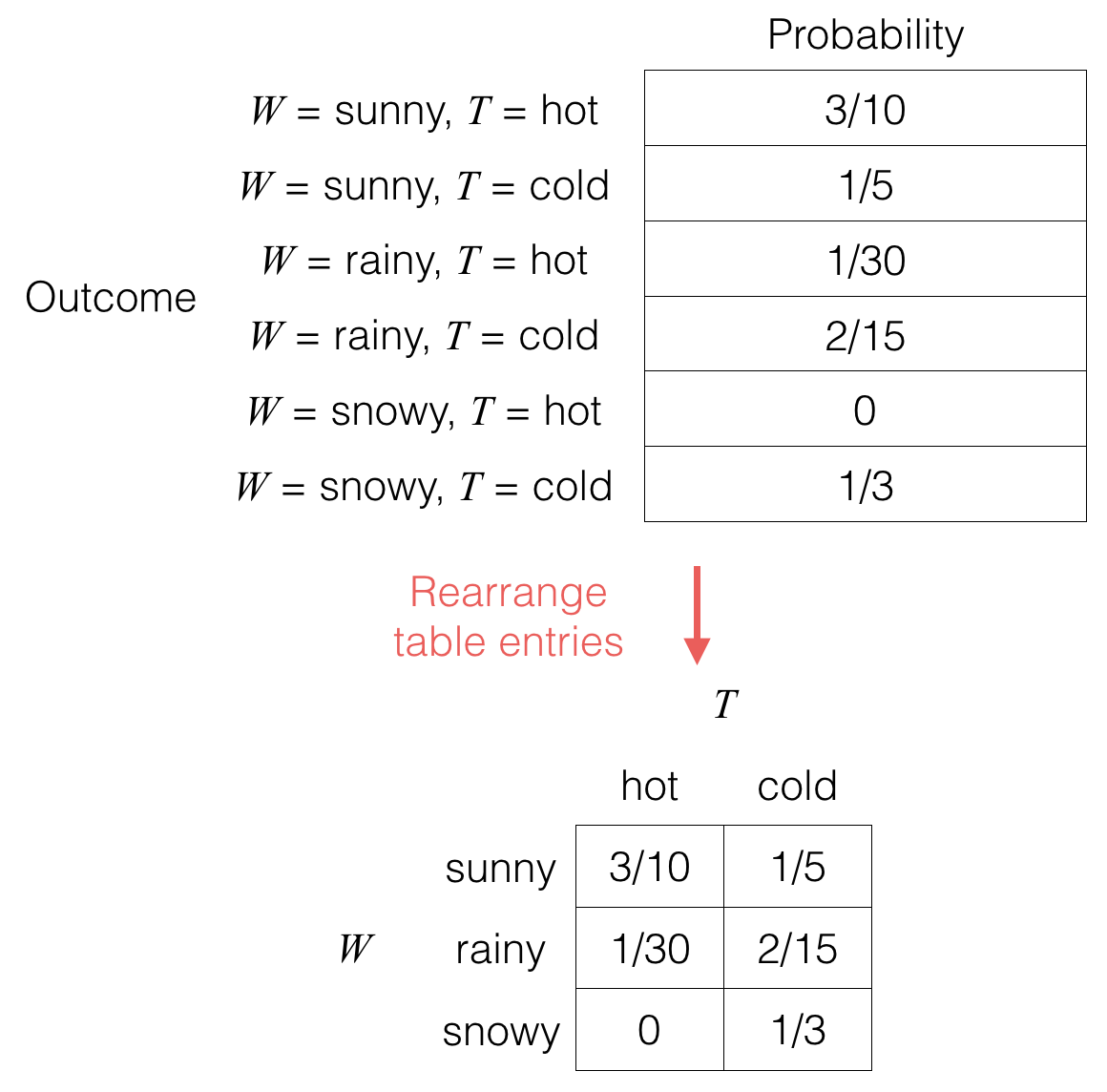

You can check that the nonnegative entries do add to 1. If we let random variable W be the weather (sunny, rainy, snowy) and random variable T be the temperature (hot, cold), then notice that we could rearrange the table in the following fashion:

When we talk about two separate random variables, we could view them either as a single “super” random variable that happens to consist of a pair of values (the first table; notice the label for each outcome corresponds to a pair of values), or we can view the two separate variables along their own different axes (the second table).

The first table tells us what the underlying probability space is, which includes what the sample space is (just read off the outcome names) and what the probability is for each of the possible outcomes for the underlying experiment at hand.

The second table is called a joint probability table pW,T for random variables W and T, and we say that random variables W and T are jointly distributed with the above distribution. Since this table is a rearrangement of the earlier table, it also consists of nonnegative entries that add to 1.

The joint probability table gives probabilities in which W and T co-occur with specific values. For example, in the above, the event that “W=sunny” and the event that “T=hot” co-occur with probability 3/10. Notationally, we write

pW,T(sunny,hot)=P(W=sunny,T=hot)=310.

Conceptual note: Given the joint probability table, we can easily go backwards and write out the first table above, which is the underlying probability space.

Preview of inference: Inference is all about answering questions like “if we observe that the weather is rainy, what is the probability that the temperature is cold?” Let’s take a look at how one might answer this question.

First, if we observe that it is rainy, then we know that “sunny” and “snowy” didn’t happen so those rows aren’t relevant anymore. So the space of possible realizations of the world has shrunk to two options now: (W=rainy,T=hot) or (W=rainy,T=cold). But what about the probabilities of these two realizations? It’s not just 1/30 and 2/15 since these don’t sum to 1 — by observing things, adjustments can be made to the probabilities of different realizations but they should still form a valid probability space.

Why not just scale both 1/30 and 2/15 by the same constant so that they sum to 1? This can be done by dividing 1/30 and 2/15 by their sum:

hot:130130+215=15,cold:215130+215=45.

Now they sum to 1. It turns out that, given that we’ved observed the weather to be rainy, these are the correct probabilities for the two options “hot” and “cold”. Let’s formalize the steps. We work backwards, first explaining what the the denominator “130+215=16” above comes from.

prob_table = {(‘sunny’, ‘hot’): 3/10, (‘sunny’, ‘cold’): 1/5, (‘rainy’, ‘hot’): 1/30, (‘rainy’, ‘cold’): 2/15, (‘snowy’, ‘hot’): 0, (‘snowy’, ‘cold’): 1/3}

prob_W_T_dict = {} for w in {‘sunny’, ‘rainy’, ‘snowy’}: prob_W_T_dict[w] = {}

prob_W_T_dict[‘sunny’][‘hot’] = 3/10 prob_W_T_dict[‘sunny’][‘cold’] = 1/5 prob_W_T_dict[‘rainy’][‘hot’] = 1/30 prob_W_T_dict[‘rainy’][‘cold’] = 2/15 prob_W_T_dict[‘snowy’][‘hot’] = 0 prob_W_T_dict[‘snowy’][‘cold’] = 1/3

comp_prob_inference.print_joint_prob_table_dict(prob_W_T_dict)

import numpy as np prob_W_T_rows = [‘sunny’, ‘rainy’, ‘snowy’] prob_W_T_cols = [‘hot’, ‘cold’] prob_W_T_array = np.array([[3/10, 1/5], [1/30, 2/15], [0, 1/3]]) comp_prob_inference.print_joint_prob_table_array(prob_W_T_array, prob_W_T_rows, prob_W_T_cols)

prob_W_T_rows = [‘sunny’, ‘rainy’, ‘snowy’] prob_W_T_cols = [‘hot’, ‘cold’] prob_W_T_row_mapping = {label: index for index, label in enumerate(prob_W_T_rows)} prob_W_T_col_mapping = {label: index for index, label in enumerate(prob_W_T_cols)} prob_W_T_array = np.array([[3/10, 1/5], [1/30, 2/15], [0, 1/3]])

Some remarks: The 2D array representation, as we’ll see soon, is very easy to work with when it comes to basic operations like summing rows, and retrieving a specific row or column. The main disadvantage of this representation is that you need to store the whole array, and if the alphabet sizes of the random variables are very large, then storing the array will take a lot of space!

The dictionaries within a dictionary representation allows for easily retrieving rows but not columns (try it: write a Python function that picks out a specific row and another function that picks out a specific column; you should see that retrieving a row is easier because it corresponds to looking at the value stored for a single key of the outer dictionary). This also means that summing a column’s probabilities is more cumbersome than summing a row’s probabilities. However, a huge advantage of this way of representing a joint probability table is that in many problems, we have a massive joint probability table that is mostly filled with 0’s. Thus, the 2D array representation would require storing a very, very large table with many 0’s, whereas the dictionaries within a dictionary representation is able to only store the nonzero table entries. We’ll see more about this issue when we look at robot localization in the second section of the course on inference in graphical models.

MARGINALIZATION: SUMMARIZING RANDOMNESS (COURSE NOTES)

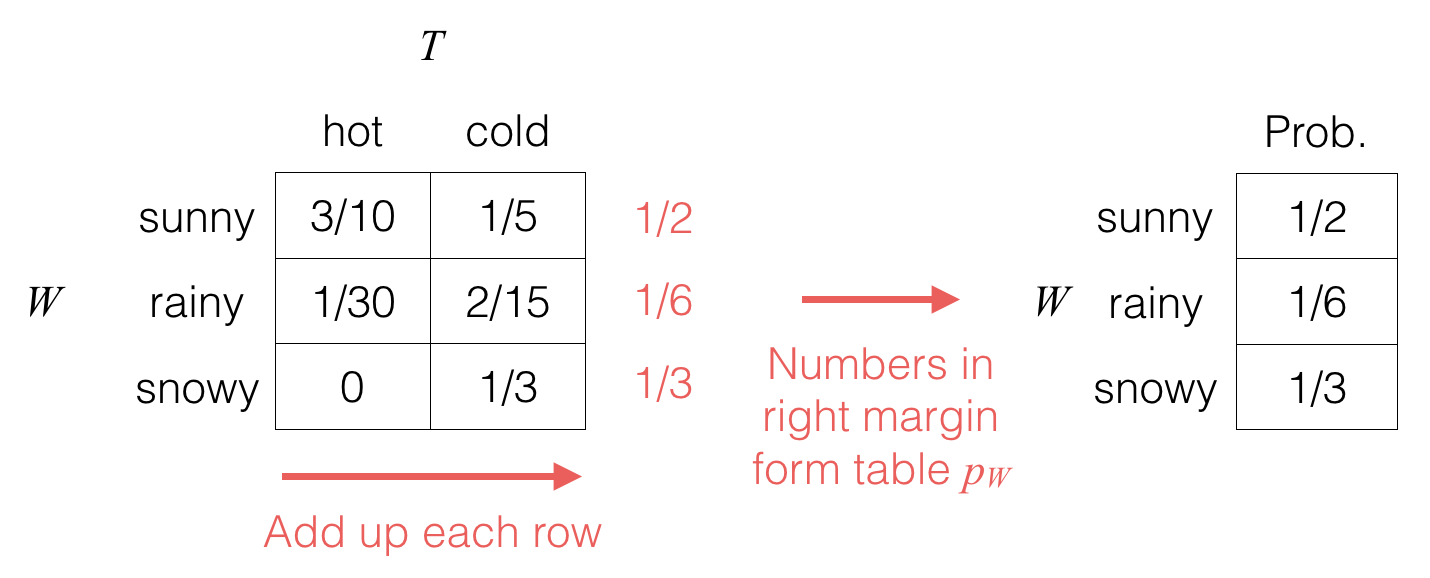

Given a joint probability table, often we’ll want to know what the probability table is for just one of the random variables. We can do this by just summing or “marginalizing” out the other random variables. For example, to get the probability table for random variable W, we do the following:

We take the joint probability table (left-hand side) and compute out the row sums (which we’ve written in the margin).

The right-hand side table is the probability table pW for random variable W; we call this resulting probability distribution the marginal distribution of W (put another way, it is the distribution obtained by marginalizing out the random variables that aren’t W).

In terms of notation, the above marginalization procedure whereby we used the joint distribution of W and T to produce the marginal distribution of W is written:

pW(w)=∑t∈TpW,T(w,t),

where T is the set of values that random variable T can take on. In fact, throughout this course, we will often omit explicitly writing out the alphabet of values that a random variable takes on, e.g., writing instead

pW(w)=∑tpW,T(w,t).

It’s clear from context that we’re summing over all possible values for t, which is going to be the values that random variable T can possibly take on.

As a specific example,

pW(rainy)=∑tpW,T(rainy,t)=pW,T(rainy,hot)⏟1/30+pW,T(rainy,cold)⏟2/15=16.

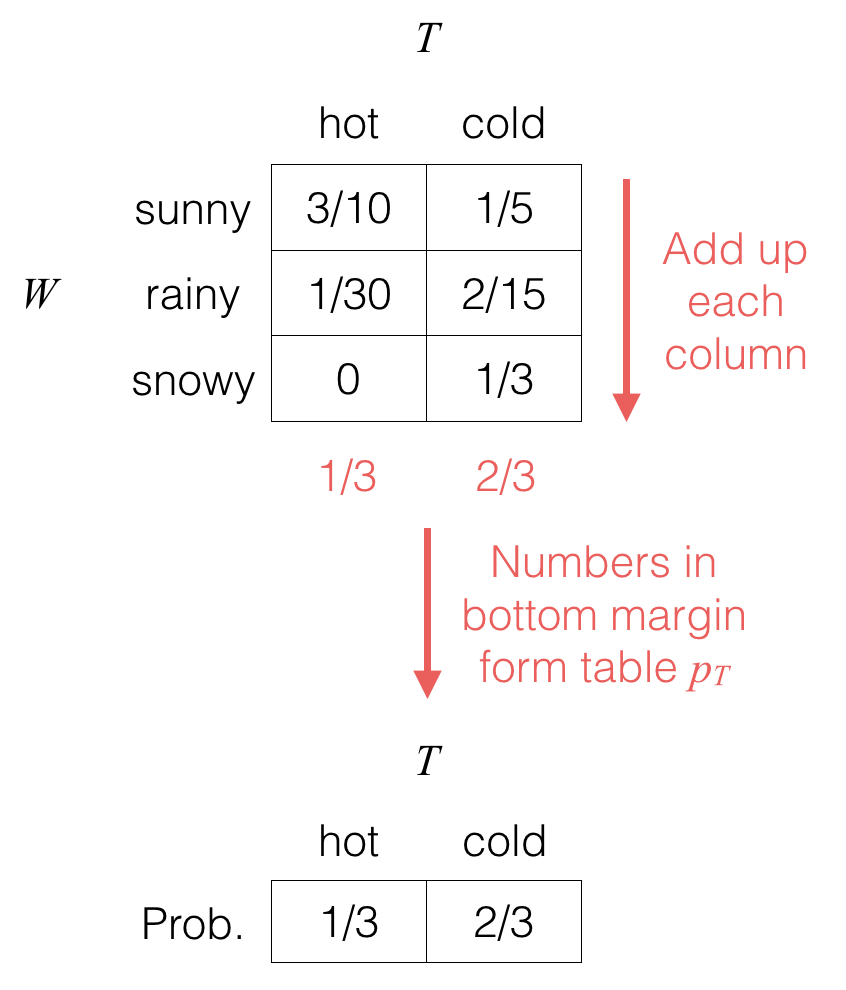

We could similarly marginalize out random variable W to get the marginal distribution pT for random variable T:

(Note that whether we write a probability table for a single variable horizontally or vertically doesn’t actually matter.)

As a formula, we would write:

pT(t)=∑wpW,T(w,t).

For example,

pT(hot)=∑wpW,T(w,hot)=pW,T(sunny,hot)⏟3/10+pW,T(rainy,hot)⏟1/30+pW,T(snowy,hot)⏟0=13.

In general:

Marginalization: Consider two random variables X and Y (that take on values in the sets X and Y respectively) with joint probability table pX,Y. For any x∈X, the marginal probability that X=x is given by

pX(x)=∑y pX,Y (x,y).

For two random variables U and V that take on values in the same alphabet, we say that U and V have the same distribution if pU(a)=pV(a) for all a.

For a pair of random variables (S,T), and another pair (U,V), we say that the pair (S,T) and the pair (U,V) have the same joint distribution if pS,T(a,b)=pU,V(a,b) for all a,b.

BAYES’ THEOREM FOR EVENTS (COURSE NOTES)

| Given two events A and B (both of which have positive probability), Bayes’ theorem, also called Bayes’ rule or Bayes’ law, gives a way to compute P(A | B) in terms of P(B | A). This result turns out to be extremely useful for inference because often times we want to compute one of these, and the other is known or otherwise straightforward to compute. |

Bayes’ theorem is given by

| P(A | B)=P(B | A)P(A)/P(B). |

The proof of why this is the case is a one liner:

| P(A | B)=(a)P(A∩B)/P(B)=(b)P(B | A)P(A)/P(B), |

| where step (a) is by the definition of conditional probability for events, and step (b) is due to the product rule for events (which follows from rearranging the definition of conditional probability for P(B | A)). |

0.001 infection

Let’s see if Bayes’ rule can help us:

There’s a slight problem. We don’t know P(T), i.e., the probability that the patient has a positive test result. But let’s break this into two cases. The patient either has the infection or not. So

We can go one step further:

So what we have is:

PRACTICE PROBLEM: BAYES’ THEOREM AND TOTAL PROBABILITY (SOLUTION)

PRACTICE PROBLEM: BAYES’ THEOREM AND TOTAL PROBABILITY (SOLUTION)

Your problem set is due in 15 minutes! It’s in one of your drawers, but they are messy, and you’re not sure which one it’s in.

The probability that the problem set is in drawer k is dk. If drawer k has the problem set and you search there, you have probability pk of finding it. There are a total of m drawers.

Suppose you search drawer i and do not find the problem set.

(a) Find the probability that the paper is in drawer j, where j≠i.

(b) Find the probability that the paper is in drawer i.

Solution: Let Ak be the event that the problem set is in drawer k, and Bk be the event that you find the problem set in drawer k.

| (a) We’ll express the desired probability as P(Aj | Bic). Since this quantity is difficult to reason about directly, we’ll use Bayes’ rule: |

| P(Aj | Bic)=P(Bic | Aj)P(Aj)P(Bic) |

| The first probability, P(Bic | Aj), expresses the probability of not finding the problem set in drawer i given that it’s in a different drawer j. Since it’s impossible to find the paper in a drawer it isn’t in, this is just 1. |

The second quantity, P(Aj), is given to us in the problem statement as dj.

The third probability, P(Bic)=1−P(Bi), is difficult to reason about directly. But, if we knew whether or not the paper was in the drawer, it would become easier. So, we’ll use total probability:

| P(Bi)=P(Bi | Ai)P(Ai)+P(Bi | Aic)P(Aic)=pidi+0(1−di) |

Putting these terms together, we find that

| P(Aj | Bic)=dj1−pidi |

Alternate method to compute the denominator P(Bic): We could use the law of total probability to decompose P(Bic) depending on which drawer the homework is actually in. We have

| P(Bic)=∑k=1mP(Ak)⏟dkP(Bic | Ak)⏟1 if k≠i,(1−pi) if k=i=∑k=1,k≠imdk+(1−pi)di=∑k=1mdk−pidi=1−pidi. |

(b) Similarly, we’ll use Bayes’ rule:

| P(Ai | Bic)=P(Bic | Ai)P(Ai)P(Bic)=(1−pi)di1−pidi |

Take-Away Lessons:

Defining the sample-space is not always going to help solve the problem. (It’s difficult to precisely define the sample space for this particular problem)

When in doubt of being able to precisely define the sample space, try to define events intelligently, i.e., in a way that you use what you’re given in the problem.

The probability law of a probability model is a function on events, or subsets of the sample space, i.e., one can work with the probability law without knowing precisely what the sample-space (as a set) is.

RELATING CONDITIONING ON EVENTS BACK TO RANDOM VARIABLES PREFACE

the conditional probability distributions for random variables that we saw previously are just a special case of conditioning on events. The next video gets into the conditional probability distribution of a random variable given that an event has occurred, which is a way that combines our use of random variables and of events.

Exercise: Bernoulli and Binomial Random Variables

a Bernoulli random variable is like a biased coin flip where probability of heads is . In particular, a Bernoulli random variables is 1 with probability , and 0 with probability . If a random variable has this particular distribution, then we write , where “” can be read as “is distributed as” or “has distribution”. Some people like to abbreviate by writing , , or even just

.

A Binomial random variable can be thought of as independent coin flips, each with probability of heads. For a random variable that has this Binomial distribution with parameters and , we denote it as , read as “ is distributed as Binomial with parameters and “. Some people might also abbreviate and instead of writing , they write or .

(a) True or false: If Y∼Binomial(1,p), then Y is a Bernoulli random variable.

Solution: The answer is true. When there’s only a single flip, counting the number if heads yields precisely the Bernoulli distribution. In particular, we have Y∼Bernoulli(p).

(b) Let’s say we have a coin that turns up heads with probability 0.6. We flip this coin 10 times. What is the probability of seeing the sequence HTHTTTTTHH, where H denotes heads and T denotes tails (so we have heads in the first toss, tails in the second, heads in the third, etc)? (Please be precise with at least 3 decimal places, unless of course the answer doesn’t need that many decimal places. You could also put a fraction.)

By independence, the sequence HTHTTTTTHH has probability

0.6×0.4×0.6×0.4×0.4×0.4×0.4×0.4×0.6×0.6=0.64×0.46.

Note that in general, if there were instead n coin flips where heads appears with probability p, then we would have pnumber of heads(1−p)n−number of heads.

(c) In the previous part, there were 4 heads and 6 tails. Did the ordering of them matter? In other words, would your answer to the previous part be the same if, for example, instead we saw the sequence HHHHTTTTTT (or any other permutation of 4 heads and 6 tails)?

Solution: As our solution to part (b) shows, the ordering of heads/tails does not matter.

(d) From the previous two parts, what we were analyzing was the same as the random variable S∼Binomial(10,0.6). Note that S=4 refers to the event that we see exactly 4 heads. Note that HTHTTTTTHH and HHHHTTTTTT are different outcomes of the underlying experiment of coin flipping. How many ways are there to see 4 heads in 10 tosses?

Solution: The number of ways to see 4 heads in 10 tosses is precisely the number of ways to choose 4 items out of 10, given by the choose operator: ${10 \choose 4} = \frac{10!}{4! 6!} = \boxed {210}$.

In general, the number of ways to see s heads in n tosses is (ns).

(e) Using your answers to parts (b) through (d), what is the probability that S=4?

Solution: There are (104)=210 ways to get 4 heads out of 10, and each way is equally likely with probability given by 0.64×0.46, so summing up the probabilities across all these ways, we have 210×0.64×0.46.

In general, for random variable S∼Binomial(n,p), the probability that S=s for s∈{0,1,…,n} is given by

It might not be a priori obvious why this probability table’s entries should sum to 1.

To show this result, we can use the Binomial Theorem, which says that for any two numbers x and y, and any nonnegative integer n,

Plugging in x=p and y=1−p, we see that the right-hand side directly corresponds to summing across all the entries of probability table pS, and the left-hand side is (p+(1−p))n=1n=1.

Exercise: The Soda Machine

A soda machine advertises 7 different flavors of soda. However, there is only one button for buying soda, which dispenses a flavor of the machine’s choosing. Adam buys 14 sodas today, and notices that they are all either grape or root beer flavored.

(a) Assuming that the soda machine actually dispenses each of its 7 flavors randomly, with equal probability, and independently each time, what is the probability that all 14 of Adam’s sodas are either grape or root beer flavored?

Solution: Let’s first consider a single soda, which could be one of 7 flavors, 2 of which are desired. Thus the probability of the soda being either grape or root beer is 27. Since each soda is dispensed independently, the probability of all 14 sodas being grape or root beer is (27)14≈2.416×10−8.

(b) How would your answer to the (a) change if the machine were out of diet cola, ginger ale, so it randomly chooses one of only 5 flavors?

Solution: If there are only 5 flavors of soda available, the probability of getting either grape or root beer is 25. Thus, once again assuming each soda is chosen independently, the probability that all 14 sodas are grape or root beer is (25)14≈2.684×10−6.

(c) What if the machine only had 3 flavors: grape, root beer, and cherry?

Solution: Similarly, with only 3 flavors to choose from, the probability becomes (23)14≈0.003425.

Independent Random Variables

Exercise: Independent Random Variables

In this exercise, we look at how to check if two random variables are independent in Python. Please make sure that you can follow the math for what’s going on and be able to do this by hand as well.

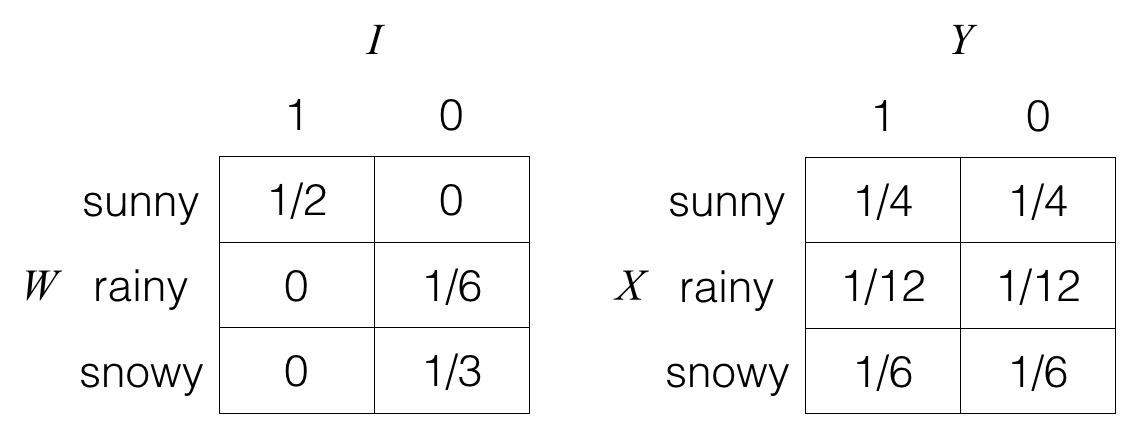

Consider random variables W, I, X, and Y, where we have shown the joint probability tables pW,I and pX,Y.

In Python:

prob_W_I = np.array([[1/2, 0], [0, 1/6], [0, 1/3]])

Note that here, we are not explicitly storing the labels, but we’ll keep track of them in our heads. The labels for the rows (in order of row index): sunny, rainy, snowy. The labels for the columns (in order of column index): 1, 0.

We can get the marginal distributions pW and pI:

prob_W = prob_W_I.sum(axis=1) prob_I = prob_W_I.sum(axis=0)

Then if W and I were actually independent, then just from their marginal distributions pW and pI, we would be able to compute the joint distribution with the formula:

If W and I are independent:pW,I(w,i)=pW(w)pI(i)for all w,i.

Note that variables prob_W and prob_I at this point store the probability tables pW and pI as 1D NumPy arrays, for which NumPy does not store whether each of these should be represented as a row or as a column.

We could however ask NumPy to treat them as column vectors, and in particular, taking the outer product of prob_W and prob_I yields what the joint distribution would be if W and I were independent:

The left-hand side is an outer product, and the right-hand side is precisely the joint probability table that would result if W and I were independent.

To compute and print the right-hand side, we do:

print(np.outer(prob_W, prob_I)) Are W and I independent (compare the joint probability table we would get if they were independent with their actual joint probability table)?

Are W and I independent (compare the joint probability table we would get if they were independent with their actual joint probability table)?

Solution: The answer is No. When you run the code above, you should see that the joint probability distribution for W and I is different from the joint probability of W and I if they were independent. In fact, if they were independent, you’d end up with the joint probability table for X and Y.

Exercise: Mutual vs Pairwise Independence

Suppose random variables X and Y are independent, where X is 1 with probability 1/2, and -1 otherwise. Similarly, Y is also 1 with probability 1/2, and -1 otherwise. In this case, we say that X and Y are identically distributed since they have the same distribution (remember, just because they have the same distribution doesn’t mean that they are the same random variable — here X and Y are independent!). Note that often in this course, we’ll be seeing random variables that are independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.).

Suppose we have another random variable Z that is the product of X and Y, i.e., Z=XY.

Select all of the following that are true:

Solution:

The fastest way to solve this problem is to realize that it’s actually the same problem as in the previous video where we had X and Y independent and identically distributed as Bernoulli(1/2), and Z was the exclusive-or (XOR) of X and Y. All we did was slightly change the labels of the outcomes to get this problem! Notice that Z takes on value -1 precisely when X and Y are different, and 1 otherwise. Hopefully that should sound like XOR. Basically -1 is what used to be 1, and 1 is what used to be 0. The problem is otherwise the same and the identical reasoning used in the video can be used here, so we won’t actually spell out the solution again in detail (it’s in the video!).

As a reminder, you can check that pX, pY, and pZ are each going to have 1/2-1/2 chance of being either 1 or -1, so they have the same distribution, and when we look at any pair of the random variables, they are going to appear independent with (1, 1), (1, -1), (-1, 1), and (-1, -1) equally likely so the pairs of random variables also have the same distribution. However, as before, when we look at all three random variables, they are not mutually independent!

MUTUAL VS PAIRWISE INDEPENDENCE TERMINOLOGY REMARK

Throughout this course, if we say that many random variables are independent (without saying which specific kind of independence), then we mean mutual independence, which we often also call marginal independenc

Conditional Independence Part 1

PRACTICE PROBLEM: CONDITIONAL INDEPENDENCE

Suppose X0,…,X100 are random variables whose joint distribution has the following factorization:

This factorization is what’s called a Markov chain. We’ll be seeing Markov chains a lot more later on in the course.

| Show that X50⊥X52 | X51. |

PRACTICE PROBLEM: CONDITIONAL INDEPENDENCE (SOLUTION)

Suppose X0,…,X100 are random variables whose joint distribution has the following factorization:

| pX0,…,X100(x0,…,x100)=pX0(x0)⋅∏i=1100pXi | Xi−1(xi | xi−1) |

This factorization is what’s called a Markov chain. We’ll be seeing Markov chains a lot more later on in the course.

| Show that X50⊥X52 | X51. |

Solution: Notice that we can marginalize out x100 as such:

Now we can repeat the same marginalization procedure to get:

(2.5) In essense, we have shown that the given joint distribution factorization applies not just to the last random variable (X100), but also up to any point in the chain.

For brevity, we will now use p(xij) as a shorthand for pXi,…,Xj(xi,…,xj). We want to exploit what we have shown to rewrite p(x5052)

where we used (2.5) for the 3rd equality and the same marginalization trick for the 5th equality. We have just shown the Markov chain property, so the conditional independence property must be satisfied.