A New Post

Probability and the Art of Modeling Uncertainty

PROBABILITY AND THE ART OF MODELING UNCERTAINTY (COURSE NOTES)

Since probability effectively corresponds to a fraction, it is a value between 0 and 1. Of course, we can have impossible events that have probability 0, or events that deterministically happen and thus have probability 1. Each time we model uncertainty in the world, there will be some underlying experiment (such as flipping a coin in our running example). An event happens with probability q∈[0,1] if in a massive number of repeats of the experiment, the event happens roughly a fraction q of the time; more repeats of the experiment make it so that the fraction gets closer to q.

Some times, an underlying experiment cannot possibly be repeated. Take for instance weather forecasting. Whereas we could actually physically flip a coin many times to repeat the same experiment, we cannot physically repeat a real-life experiment for what different realizations of tomorrow’s weather will be. We could wait until tomorrow to see the weather, but then we would need a time machine to go back in time by one day to repeat and see what the weather is like tomorrow (and this assumes that there’s some inherent randomness in tomorrow’s weather)! In such a case, our only hope is to somehow model or simulate tomorrow’s weather given measurements up to present time.

A good model

Different people could model the same real world problem differently! Throughout the course, a recurring challenge in building computer programs that reason probabilistically is figuring out how to model real-world problems. A good model — even if not actually accurate in describing, for instance, the science behind weather — enables us to make good predictions.

Once a weather forecaster has anchored some way of modeling or simulating weather, then if it claims that there’s a 30% chance of rain tomorrow, we could interpret this as saying that using their way of simulating tomorrow’s weather, in roughly 30% of simulated results for tomorrow’s weather, there is rain.

A probability is a number that is at least 0 and at most 1.

There is only one way to model tomorrow’s weather. False: Different people can model weather differently, leading to different forecasts.

Let’s say I have a coin that, when tossed, is heads with probability 0.7. Select all the statements below which are true.

If we flip the coin 10 times, it is possible that none of them are heads. As we increase the number of times we flip the coin, the fraction of coin flips that are heads becomes closer to 0.7.

If we flip the coin 10 times, it is indeed possible that none of them are heads. In fact, even if we flip the coin 1,000,000 times, it is still possible that none of them are heads albeit such an outcome is extremely unlikely (by the end of this first section of the course, you’ll be able to calculuate just how unlikely). In particular, it does not have to be the case that with 1,000 flips, there will be exactly 700 heads, or that even with 1,000,000 flips, there will be exactly 700,000 heads. However, as we increase the number of flips, the fraction of coin flips that are heads will indeed become closer to 0.7.

TWO INGREDIENTS TO MODELING UNCERTAINTY (COURSE NOTES)

When we think of an uncertain world, we will always think of there being some underlying experiment of interest. To model this uncertain world, it suffices to keep track of two things:

The set of all possible outcomes for the experiment: this set is called the sample space and is usually denoted by the Greek letter Omega Ω. (For the fair coin flip, there are exactly two possible outcomes: heads, tails. Thus, Ω={heads,tails}.)

The probability of each outcome: for each possible outcome, assign a probability that is at least 0 and at most 1. (For the fair coin flip, P(heads)=12 and P(tails)=12.)

Notation: Throughout this course, for any statement S, “P(S)” denotes the probability of S happening.

In Python:

model = {‘heads’: 1/2, ‘tails’: 1/2} In particular, we see that we can model uncertainty in code using a Python dictionary. The sample space is precisely the keys in the dictionary:

sample_space = set(model.keys()) {‘tails’, ‘heads’} Of course, the dictionary gives us the assignment of probabilities, meaning that for each outcome in the sample space (i.e., for each key in the dictionary), we have an assigned probability:

model[‘heads’] 0.5 model[‘tails’] 0.5 A few important remarks:

-

The sample space is always specified to be collectively exhaustive, meaning that every possible outcome is in it, and mutually exclusive, meaning that once the experiment is run (e.g., flipping the fair coin), exactly one possible outcome in the sample space happens. It’s impossible for multiple outcomes in the sample space to simultaneously happen! It’s also impossible for none of the outcomes to happen!

-

Probabilities can be thought of as fractions of times outcomes occur; thus, probabilities are nonnegative and at least 0 and at most 1.

-

If we add up the probabilities of all the possible outcomes in the sample space, we get 1. (For the fair coin flip, P(heads)+P(tails)=12+12=1.)

Some intuition for this: Consider the coin flipping experiment. What does the fraction of times heads occur and the fraction of times tails occur add up to? Since these are the only two possible outcomes (and again, recall that these outcomes are exclusive in that they can’t simultaneously occur, and exhaustive since they are the only possible outcomes), these two fractions will always sum to 1. For a massive number of repeats of the experiment, these two fractions correspond to P(heads) and P(tails); the fractions sum to 1 and so these probabilities also sum to 1.

Recall that for each key in a Python dictionary, there is an associated value. A Python dictionary stores a valid probability distribution when the values are each at least 0 and at most 1; moreover, when we add up the values for all the keys, the sum is equal to 1.

How a sample space is chosen is not unique. As a more involved example, we could even have a sample space that consists of two fair six-sided dice being thrown, where we basically discard all the information about the second die’s outcome to reason about the first die. We could also add junk outcomes that are assigned probability 0. However, in general, it’s best to keep the sample space as simple as possible to solve the problem at hand.

Suppose we use the sample space {1,2,3,4,5,6}. Write the Python dictionary that encodes a valid probabilistic model for the fair die roll experiment using this sample space. (Your answer should be the Python dictionary itself, and not the dictionary assigned to a variable, so please do not include, for instance “model =” before specifying your answer. Also please be accurate with your fractions up to 5 decimals.)

Assign each outcome probability 1/6: {1: 1/6, 2: 1/6, 3: 1/6, 4: 1/6, 5: 1/6, 6: 1/6}

PROBABILITY SPACES (COURSE NOTES)

At this point, we’ve actually already seen the most basic data structure used throughout this course for modeling uncertainty, called a finite probability space (in this course, we’ll often also just call this either a probability space or a probability model):

A finite probability space consists of two ingredients:

-

a sample space Ω consisting of a finite (i.e., not infinite) number of collectively exhaustive and mutually exclusive possible outcomes

-

an assignment of probabilities: for each possible outcome ω∈Ω, we assign a probability P(outcome ω) at least 0 and at most 1, where we require that the probabilities across all the possible outcomes in the sample space add up to 1:

∑ω∈ΩP(outcome ω)=1.

Notation: As shorthand we occasionally use the tuple “(Ω,P)” to refer to a finite probability space to remind ourselves of the two ingredients needed, sample space Ω and an assignment of probabilities P. As we already saw, in code these two pieces can be represented together in a single Python dictionary. However, when we want to reason about probability spaces in terms of the mathematics, it’s helpful to have names for the two pieces.

Why finite? Of the two pieces making up a finite probability space (Ω,P), the sample space Ω being finite is a fairly natural constraint, corresponding to how we typically work with Python dictionaries where there is only a finite number of keys. As we’ll see, finite probability spaces are already extremely useful in practice. Pedagogically, finite probability spaces also provide a great intro to probability theory as they already carry a wealth of intuition, much of which carries over to a more complete story of general probability spaces!

TABLE REPRESENTATION (COURSE NOTES)

A probability space is a data structure in that we can always visualize as a table of nonnegative entries that sum to 1. Let’s see a concrete example of this, first writing the table out on paper and then coding it up.

Example: Suppose we have a model of tomorrow’s weather given as follows: sunny with probability 1/2, rainy with probability 1/6, and snowy with probability 1/3. Here’s the probability space, shown as a table:

Probability sunny 1/2Outcome rainy 1/6

snowy 1/3 Note: This a table of 3 nonnegative entries that sum to 1. The rows correspond to the sample space Ω={sunny,rainy,snowy}.

We will often use this table representation of a probability space to tell you how we’re modeling uncertainty for a particular problem. It provides the simplest of visualizations of a probability space.

Of course, in Python code, the above probability space is given by:

prob_space = {‘sunny’: 1/2, ‘rainy’: 1/6, ‘snowy’: 1/3} A different way to code up the same probability space is to separately specify the outcomes (i.e., the sample space) and the probabilities:

outcomes = [‘sunny’, ‘rainy’, ‘snowy’] probabilities = np.array([1/2, 1/6, 1/3]) The i-th entry of outcomes has probability given by the i-th entry of probabilities. Note that probabilities is a vector of numbers that we represent as a Numpy array. Numpy has various built-in methods that enable us to easily work with vectors (and more generally arrays) of numbers.

ADDENDUM: MORE ON SAMPLE SPACES

In the video, we saw that a sample space encoding the outcomes of 2 coin flips encodes all the information for 1 coin flip as well. Thus, we could use the same sample space to model a single coin flip. However, if we really only cared about a single coin flip, then a sample space encoding 2 coin flips is richer than we actually need it to be!

When we model some uncertain situation, how we specify a sample space is not unique. We saw an example of this already in an earlier exercise where for rolling a single six-sided die, we can choose to name the outcomes differently, saying for instance “roll 1” instead of “1”. We could even add a bunch of extraneous outcomes that all have probability 0. We could add extraneous information that doesn’t matter such as “Alice rolls 1”, “Bob rolls 1”, etc where we enumerate out all the people who could roll the die in which the outcome is a 1. Sure, depending on the problem we are trying to solve, maybe knowing who rolled the die is important, but if we don’t care about who rolled the die, then the information isn’t helpful but it’s still possible to include this information in the sample space.

Generally speaking it’s best to choose a sample space that is as simple as possible for modeling what we care about solving. For example, if we were rolling a six-sided die, and we actually only care about whether the face shows up at least 4 or not, then it’s sufficient to just keep track of two outcomes, “at least 4” and “less than 4”.

Event

Subset of sample space

ADDENDUM: CODE FOR DEALING WITH SETS IN PYTHON

In the video, the set operations can actually be implemented in Python as follows:

sample_space = {‘HH’, ‘HT’, ‘TH’, ‘TT’} A = {‘HT’, ‘TT’} B = {‘HH’, ‘HT’, ‘TH’} C = {‘HH’} A_intersect_B = A.intersection(B) # equivalent to “B.intersection(A)” or “A & B” A_union_C = A.union(C) # equivalent to “C.union(A)” and also “A | C” B_complement = sample_space.difference(B) # equivalent also to “sample_space - B”

ADDENDUM: PROBABILITIES WITH EVENTS AND CODE

From the videos, we see that an event is a subset of the sample space Ω. If you remember our table representation for a probability space, then an event could be thought of as a subset of the rows, and the probability of the event is just the sum of the probability values in those rows!

The probability of an event A⊆Ω is the sum of the probabilities of the possible outcomes in A:

P(A)≜∑ω∈A P(outcome ω),

where “≜” means “defined as”.

We can translate the above equation into Python code. In particular, we can compute the probability of an event encoded as a Python set event, where the probability space is encoded as a Python dictionary prob_space:

def prob_of_event(event, prob_space): total = 0 for outcome in event: total += prob_space[outcome] return total Here’s an example of how to use the above function:

prob_space = {‘sunny’: 1/2, ‘rainy’: 1/6, ‘snowy’: 1/3} rainy_or_snowy_event = {‘rainy’, ‘snowy’} print(prob_of_event(rainy_or_snowy_event, prob_space))

| In general, suppose that a probability space has m (not infinite) different possible outcomes, i.e., the sample space Ω has size | Ω | =m. How many events are there, in terms of m? |

There are 2^m possibilities. To count the number of events, note that to form each event, we go through each of the m possible outcomes and we either include the outcome or not. Thus, the total number of possible events is:

2 (whether we include the first outcome or not) multiplied by 2 (whether we include the second outcome or not) multiplied by … finally multiplied by 2 (whether we include the m-th outcome or not) = 2m.

A FIRST LOOK AT “RANDOM VARIABLES”

Follow along in an IPython prompt.

We continue with our weather example.

prob_space = {‘sunny’: 1/2, ‘rainy’: 1/6, ‘snowy’: 1/3}

We can simulate tomorrow’s weather using the above model of the world. Let’s simulate two different values, one (which we’ll call W for “weather”) for whether tomorrow will be sunny, rainy, or snowy, and another (which we’ll call I for “indicator”) that is 1 if it is sunny and 0 otherwise:

random_outcome = comp_prob_inference.sample_from_finite_probability_space(prob_space) W = random_outcome if random_outcome == ‘sunny’: I = 1 else: I = 0

Print out the variables W or I to see that they take on specific values. Then re-run the above block of code a few times.

You should see that W and I change and are random (following the probabilities given by the probability space).

This code shows something that’s of key importance that we’ll see throughout the course. Variables W and I store the values of what are called random variables.

RANDOM VARIABLES (COURSE NOTES)

To mathematically reason about a random variable, we need to somehow keep track of the full range of possibilities for what the random variable’s value could be, and how probable different instantiations of the random variable are. The resulting formalism may at first seem a bit odd but as we progress through the course, it will become more apparent how this formalism helps us study real-world problems and address these problems with powerful solutions.

To build up to the formalism, first note, computationally, what happened in the code in the previous part.

First, there is an underlying probability space (Ω,P), where Ω={sunny,rainy,snowy}, and

P(sunny)=1/2,P(rainy)=1/6,P(snowy)=1/3. A random outcome ω∈Ω is sampled using the probabilities given by the probability space (Ω,P). This step corresponds to an underlying experiment happening.

Two random variables are generated:

W is set to be equal to ω. As an equation:

W(ω)=ωfor ω∈{sunny,rainy,snowy}. This step perhaps seems entirely unnecessary, as you might wonder “Why not just call the random outcome W instead of ω?” Indeed, this step isn’t actually necessary for this particular example, but the formalism for random variables has this step to deal with what happens when we encounter a random variable like I.

I is set to 1 if ω=sunny, and 0 otherwise. As an equation:

I(ω)={1if ω=sunny,0if ω∈{rainy,snowy}. Importantly, multiple possible outcomes (rainy or snowy) get mapped to the same value 0 that I can take on.

We see that random variable W maps the sample space Ω={sunny,rainy,snowy} to the same set {sunny,rainy,snowy}. Meanwhile, random variable I maps the sample space Ω={sunny,rainy,snowy} to the set {0,1}.

In general:

Definition of a “finite random variable” (in this course, we will just call this a “random variable”): Given a finite probability space (Ω,P), a finite random variable X is a mapping from the sample space Ω to a set of values X that random variable X can take on. (We will often call X the “alphabet” of random variable X.)

For example, random variable W takes on values in the alphabet {sunny,rainy,snowy}, and random variable I takes on values in the alphabet {0,1}.

Quick summary: There’s an underlying experiment corresponding to probability space (Ω,P). Once the experiment is run, let ω∈Ω denote the outcome of the experiment. Then the random variable takes on the specific value of X(ω)∈X.

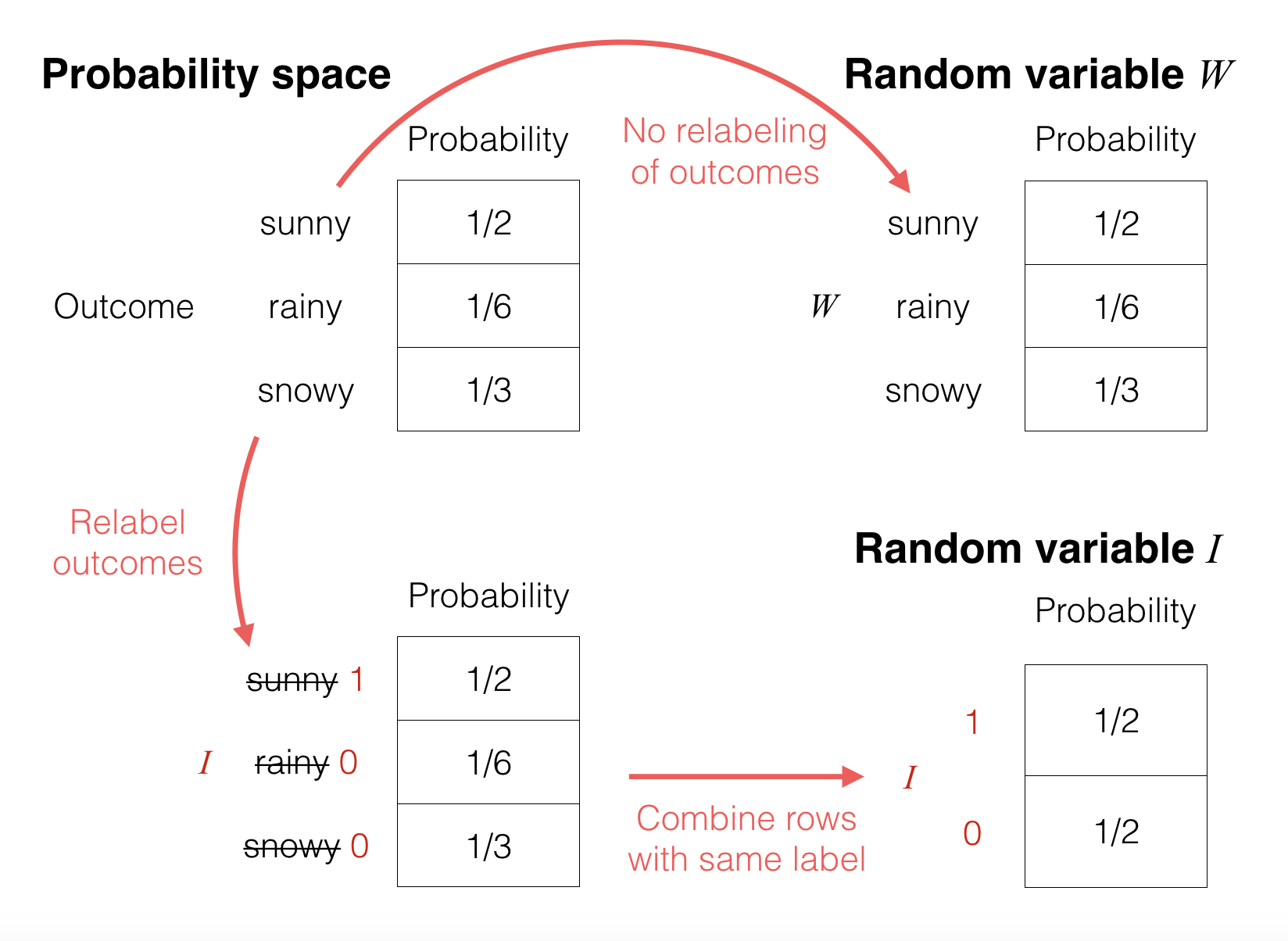

Explanation using a picture: Continuing with the weather example, we can pictorially see what’s going on by looking at the probability tables for: the original probability space, the random variable W, and the random variable I:

These tables make it clear that a “random variable” really is just reassigning/relabeling what the values are for the possible outcomes in the underlying probability space (given by the top left table):

-

In the top right table, random variable W does not do any sort of relabeling so its probability table looks the same as that of the underlying probability space.

-

In the bottom left table, the random variable Irelabels/reassigns “sunny” to 1, and both “rainy” and “snowy” to 0. Intuitively, since two of the rows now have the same label 0, it makes sense to just combine these two rows, adding their probabilities (16+13=12). This results in the bottom right table.

Technical note: Even though the formal definition of a finite random variable doesn’t actually make use of the probability assignment P, the probability assignment will become essential as soon as we talk about how probability works with random variables.

RANDOM VARIABLES NOTATION AND TERMINOLOGY (COURSE NOTES)

In this course, we denote random variables with capital/uppercase letters, such as X, W, I, etc. We use the phrases “probability table”, “probability mass function” (abbreviated as PMF), and “probability distribution” (often simply called a distribution) to mean the same thing, and in particular we denote the probability table for X to be pX or pX(⋅).

We write pX(x) to denote the entry of the probability table that has label x∈X where X is the set of values that random variable X takes on. Note that we use lowercase letters like x to denote variables storing nonrandom values. We can also look up values in a probability table using specific outcomes, e.g., from earlier, we have pW(rainy)=1/6 and pI(1)=1/2.

Note that we use the same notation as in math where a function f might also be written as f(⋅) to explicitly indicate that it is the function of one variable. Both f and f(⋅) refer to a function whereas f(x) refers to the value of the function f evaluated at the point x.

As an example of how to use all this notation, recall that a probability table consists of nonnegative entries that add up to 1. In fact, each of the entries is at most 1 (otherwise the numbers would add to more than 1). For a random variable X taking on values in X, we can write out these constraints as:

0≤pX(x)≤1for all x∈X,∑x∈XpX(x)=1.

Often in the course, if we are making statements about all possible outcomes of X, we will omit writing out thealphabet X explicitly. For example, instead of the above, we might write the following equivalent statement:

0≤pX(x)≤1for all x,∑xpX(x)=1.

U and V have the same PMF but they are associated with different probability spaces.

In general, for a real-valued function g (i.e., it maps real numbers to real numbers), is g(f(W)) a random variable?

Yes: g just relabels the outcome labels of the probability table for f(W).

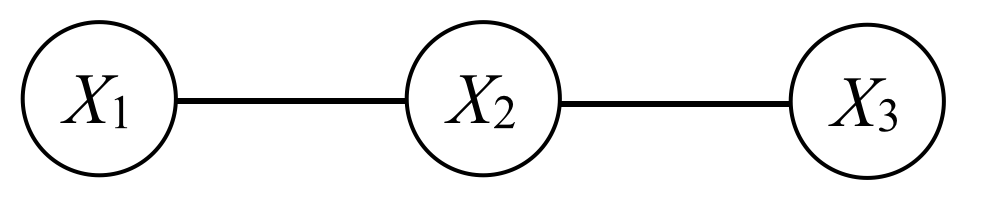

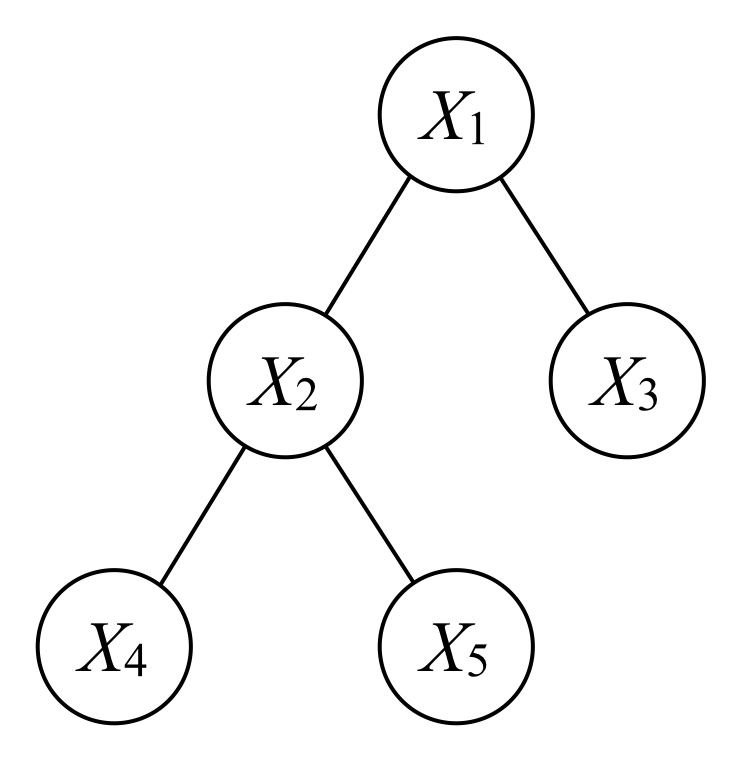

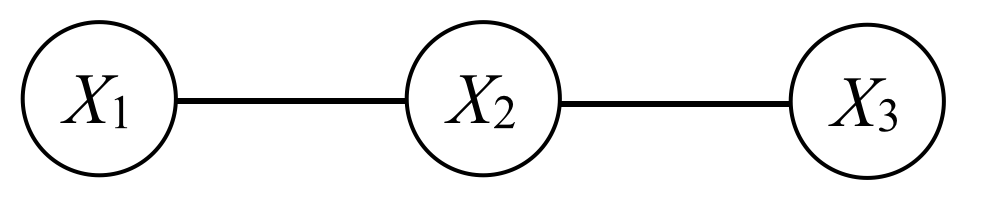

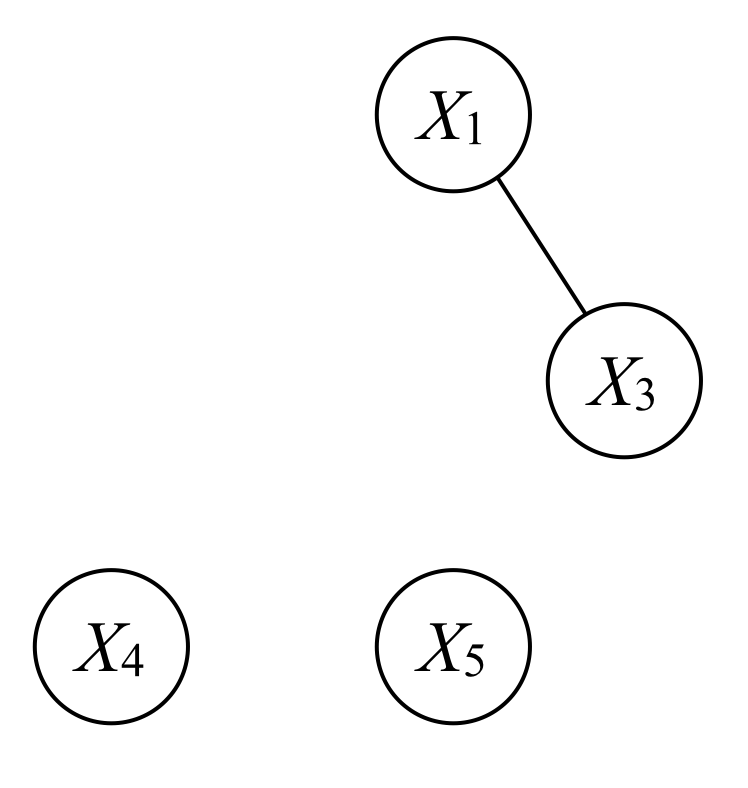

RELATING TWO RANDOM VARIABLES (COURSE NOTES)

At the most basic level, inference refers to using an observation to reason about some unknown quantity. In this course, the observation and the unknown quantity are represented by random variables. The main modeling question is: How do these random variables relate?

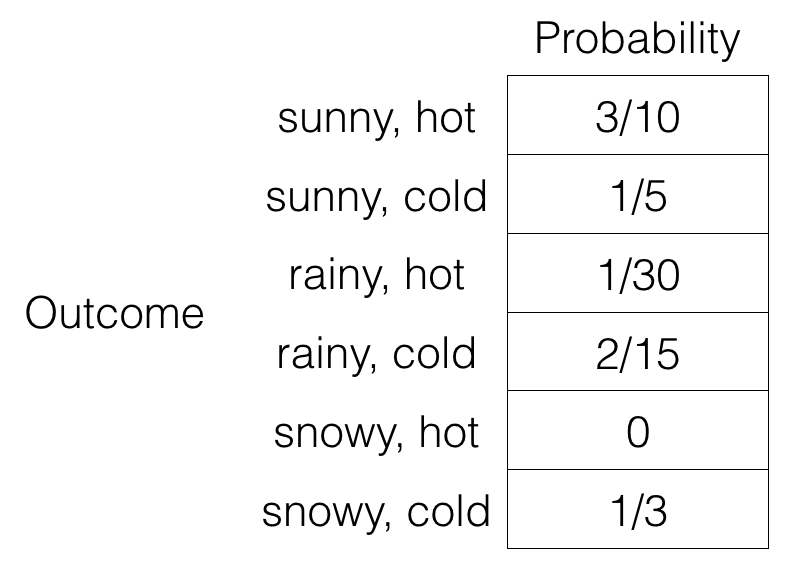

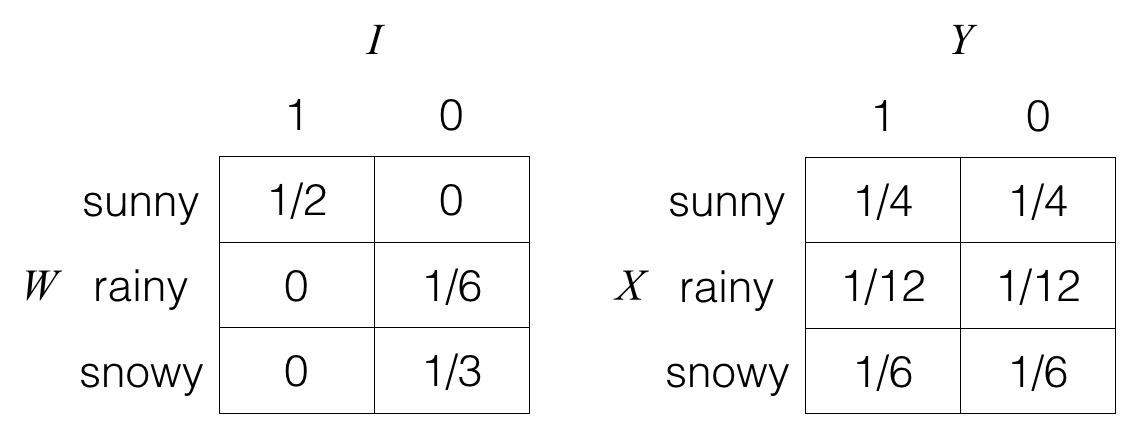

Let’s build on our earlier weather example, where now another outcome of interest appears, the temperature, which we quantize into to possible values “hot” and “cold”. Let’s suppose that we have the following probability space:

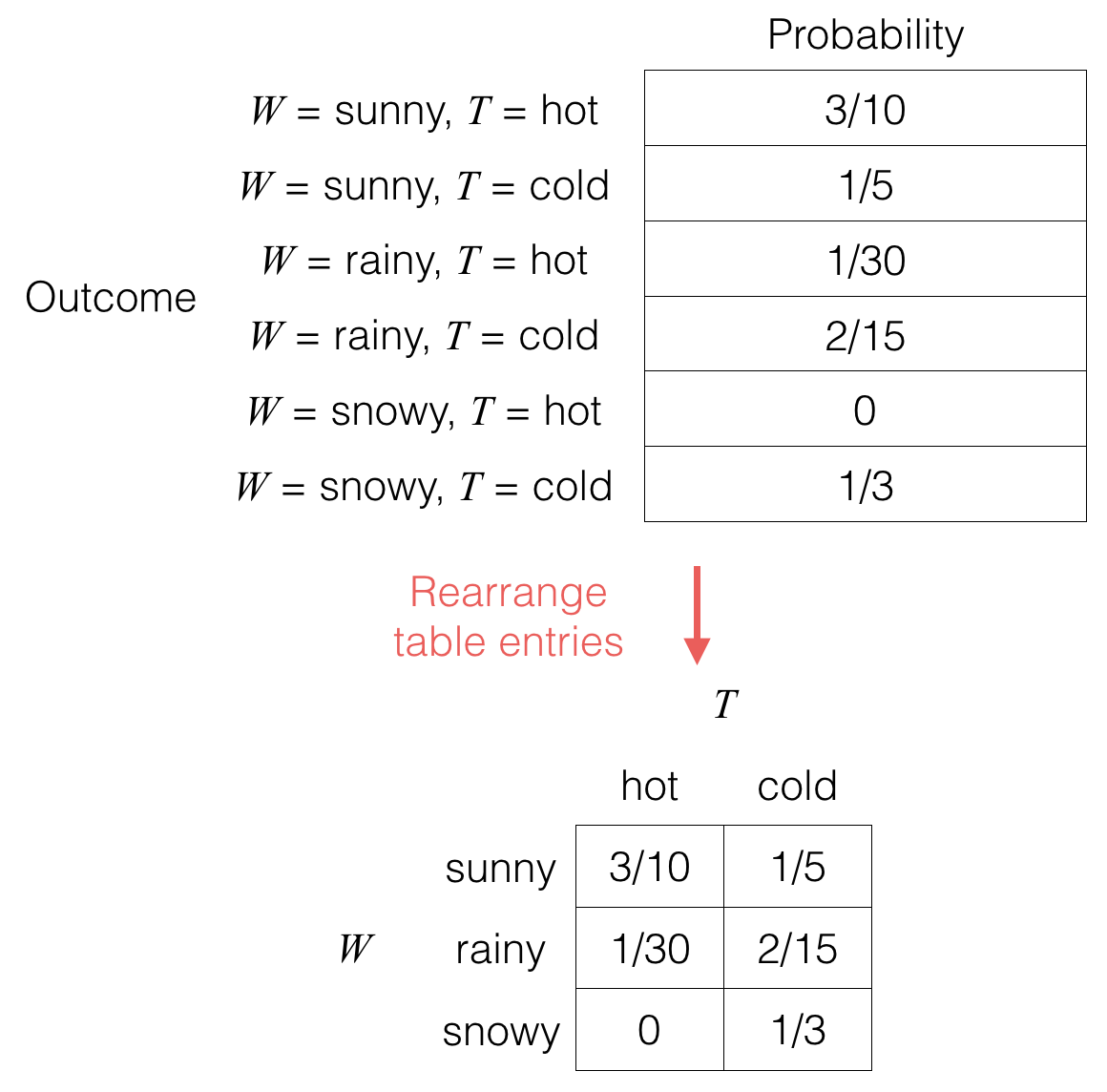

You can check that the nonnegative entries do add to 1. If we let random variable W be the weather (sunny, rainy, snowy) and random variable T be the temperature (hot, cold), then notice that we could rearrange the table in the following fashion:

When we talk about two separate random variables, we could view them either as a single “super” random variable that happens to consist of a pair of values (the first table; notice the label for each outcome corresponds to a pair of values), or we can view the two separate variables along their own different axes (the second table).

The first table tells us what the underlying probability space is, which includes what the sample space is (just read off the outcome names) and what the probability is for each of the possible outcomes for the underlying experiment at hand.

The second table is called a joint probability table pW,T for random variables W and T, and we say that random variables W and T are jointly distributed with the above distribution. Since this table is a rearrangement of the earlier table, it also consists of nonnegative entries that add to 1.

The joint probability table gives probabilities in which W and T co-occur with specific values. For example, in the above, the event that “W=sunny” and the event that “T=hot” co-occur with probability 3/10. Notationally, we write

pW,T(sunny,hot)=P(W=sunny,T=hot)=310.

Conceptual note: Given the joint probability table, we can easily go backwards and write out the first table above, which is the underlying probability space.

Preview of inference: Inference is all about answering questions like “if we observe that the weather is rainy, what is the probability that the temperature is cold?” Let’s take a look at how one might answer this question.

First, if we observe that it is rainy, then we know that “sunny” and “snowy” didn’t happen so those rows aren’t relevant anymore. So the space of possible realizations of the world has shrunk to two options now: (W=rainy,T=hot) or (W=rainy,T=cold). But what about the probabilities of these two realizations? It’s not just 1/30 and 2/15 since these don’t sum to 1 — by observing things, adjustments can be made to the probabilities of different realizations but they should still form a valid probability space.

Why not just scale both 1/30 and 2/15 by the same constant so that they sum to 1? This can be done by dividing 1/30 and 2/15 by their sum:

hot:130130+215=15,cold:215130+215=45.

Now they sum to 1. It turns out that, given that we’ved observed the weather to be rainy, these are the correct probabilities for the two options “hot” and “cold”. Let’s formalize the steps. We work backwards, first explaining what the the denominator “130+215=16” above comes from.

prob_table = {(‘sunny’, ‘hot’): 3/10, (‘sunny’, ‘cold’): 1/5, (‘rainy’, ‘hot’): 1/30, (‘rainy’, ‘cold’): 2/15, (‘snowy’, ‘hot’): 0, (‘snowy’, ‘cold’): 1/3}

prob_W_T_dict = {} for w in {‘sunny’, ‘rainy’, ‘snowy’}: prob_W_T_dict[w] = {}

prob_W_T_dict[‘sunny’][‘hot’] = 3/10 prob_W_T_dict[‘sunny’][‘cold’] = 1/5 prob_W_T_dict[‘rainy’][‘hot’] = 1/30 prob_W_T_dict[‘rainy’][‘cold’] = 2/15 prob_W_T_dict[‘snowy’][‘hot’] = 0 prob_W_T_dict[‘snowy’][‘cold’] = 1/3

comp_prob_inference.print_joint_prob_table_dict(prob_W_T_dict)

import numpy as np prob_W_T_rows = [‘sunny’, ‘rainy’, ‘snowy’] prob_W_T_cols = [‘hot’, ‘cold’] prob_W_T_array = np.array([[3/10, 1/5], [1/30, 2/15], [0, 1/3]]) comp_prob_inference.print_joint_prob_table_array(prob_W_T_array, prob_W_T_rows, prob_W_T_cols)

prob_W_T_rows = [‘sunny’, ‘rainy’, ‘snowy’] prob_W_T_cols = [‘hot’, ‘cold’] prob_W_T_row_mapping = {label: index for index, label in enumerate(prob_W_T_rows)} prob_W_T_col_mapping = {label: index for index, label in enumerate(prob_W_T_cols)} prob_W_T_array = np.array([[3/10, 1/5], [1/30, 2/15], [0, 1/3]])

Some remarks: The 2D array representation, as we’ll see soon, is very easy to work with when it comes to basic operations like summing rows, and retrieving a specific row or column. The main disadvantage of this representation is that you need to store the whole array, and if the alphabet sizes of the random variables are very large, then storing the array will take a lot of space!

The dictionaries within a dictionary representation allows for easily retrieving rows but not columns (try it: write a Python function that picks out a specific row and another function that picks out a specific column; you should see that retrieving a row is easier because it corresponds to looking at the value stored for a single key of the outer dictionary). This also means that summing a column’s probabilities is more cumbersome than summing a row’s probabilities. However, a huge advantage of this way of representing a joint probability table is that in many problems, we have a massive joint probability table that is mostly filled with 0’s. Thus, the 2D array representation would require storing a very, very large table with many 0’s, whereas the dictionaries within a dictionary representation is able to only store the nonzero table entries. We’ll see more about this issue when we look at robot localization in the second section of the course on inference in graphical models.

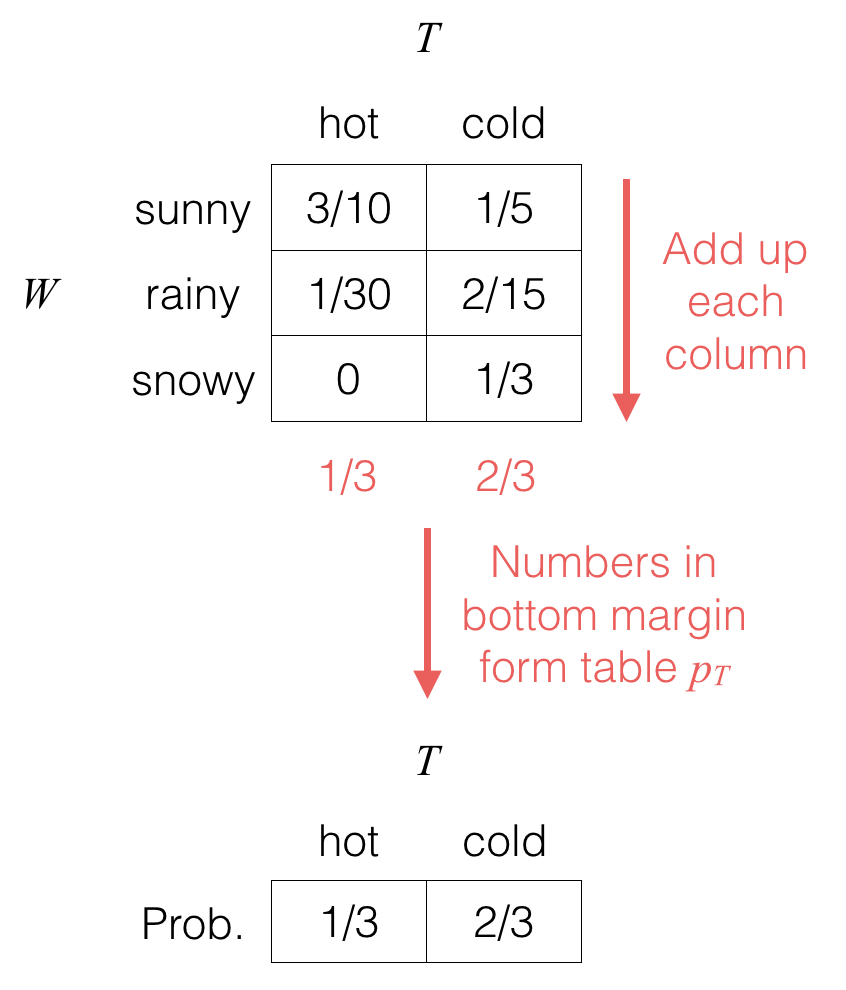

MARGINALIZATION: SUMMARIZING RANDOMNESS (COURSE NOTES)

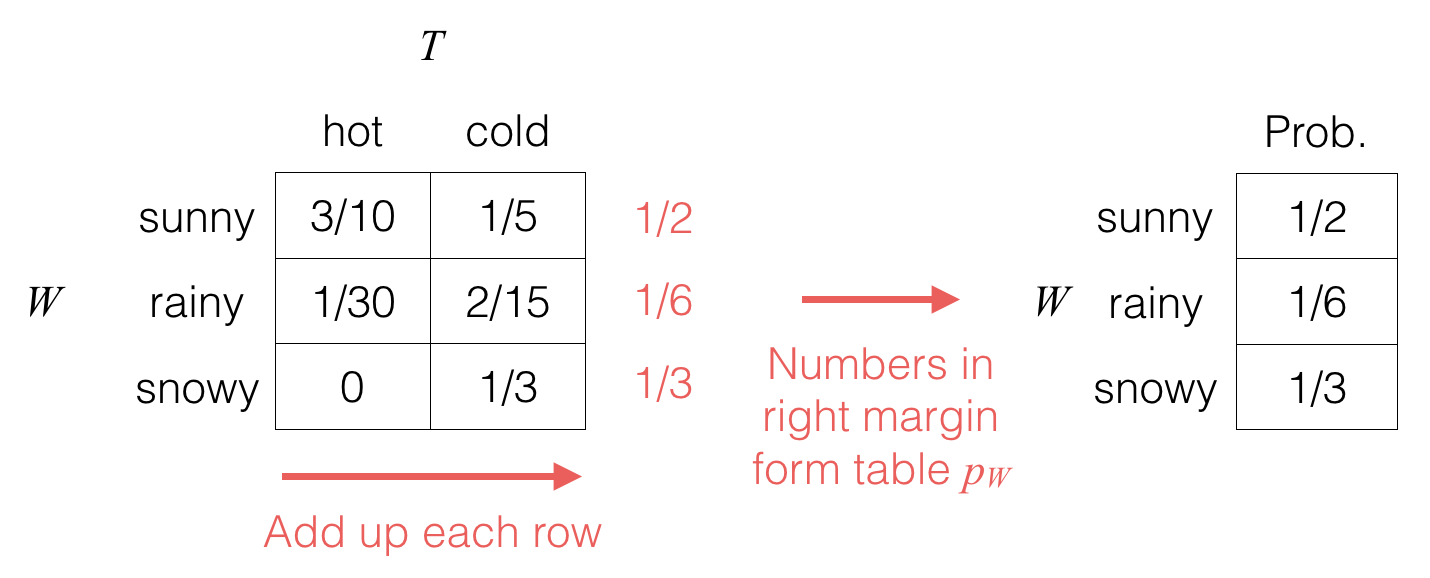

Given a joint probability table, often we’ll want to know what the probability table is for just one of the random variables. We can do this by just summing or “marginalizing” out the other random variables. For example, to get the probability table for random variable W, we do the following:

We take the joint probability table (left-hand side) and compute out the row sums (which we’ve written in the margin).

The right-hand side table is the probability table pW for random variable W; we call this resulting probability distribution the marginal distribution of W (put another way, it is the distribution obtained by marginalizing out the random variables that aren’t W).

In terms of notation, the above marginalization procedure whereby we used the joint distribution of W and T to produce the marginal distribution of W is written:

pW(w)=∑t∈TpW,T(w,t),

where T is the set of values that random variable T can take on. In fact, throughout this course, we will often omit explicitly writing out the alphabet of values that a random variable takes on, e.g., writing instead

pW(w)=∑tpW,T(w,t).

It’s clear from context that we’re summing over all possible values for t, which is going to be the values that random variable T can possibly take on.

As a specific example,

pW(rainy)=∑tpW,T(rainy,t)=pW,T(rainy,hot)⏟1/30+pW,T(rainy,cold)⏟2/15=16.

We could similarly marginalize out random variable W to get the marginal distribution pT for random variable T:

(Note that whether we write a probability table for a single variable horizontally or vertically doesn’t actually matter.)

As a formula, we would write:

pT(t)=∑wpW,T(w,t).

For example,

pT(hot)=∑wpW,T(w,hot)=pW,T(sunny,hot)⏟3/10+pW,T(rainy,hot)⏟1/30+pW,T(snowy,hot)⏟0=13.

In general:

Marginalization: Consider two random variables X and Y (that take on values in the sets X and Y respectively) with joint probability table pX,Y. For any x∈X, the marginal probability that X=x is given by

pX(x)=∑y pX,Y (x,y).

For two random variables U and V that take on values in the same alphabet, we say that U and V have the same distribution if pU(a)=pV(a) for all a.

For a pair of random variables (S,T), and another pair (U,V), we say that the pair (S,T) and the pair (U,V) have the same joint distribution if pS,T(a,b)=pU,V(a,b) for all a,b.

BAYES’ THEOREM FOR EVENTS (COURSE NOTES)

| Given two events A and B (both of which have positive probability), Bayes’ theorem, also called Bayes’ rule or Bayes’ law, gives a way to compute P(A | B) in terms of P(B | A). This result turns out to be extremely useful for inference because often times we want to compute one of these, and the other is known or otherwise straightforward to compute. |

Bayes’ theorem is given by

| P(A | B)=P(B | A)P(A)/P(B). |

The proof of why this is the case is a one liner:

| P(A | B)=(a)P(A∩B)/P(B)=(b)P(B | A)P(A)/P(B), |

| where step (a) is by the definition of conditional probability for events, and step (b) is due to the product rule for events (which follows from rearranging the definition of conditional probability for P(B | A)). |

0.001 infection

Let’s see if Bayes’ rule can help us:

There’s a slight problem. We don’t know P(T), i.e., the probability that the patient has a positive test result. But let’s break this into two cases. The patient either has the infection or not. So

We can go one step further:

So what we have is:

PRACTICE PROBLEM: BAYES’ THEOREM AND TOTAL PROBABILITY (SOLUTION)

PRACTICE PROBLEM: BAYES’ THEOREM AND TOTAL PROBABILITY (SOLUTION)

Your problem set is due in 15 minutes! It’s in one of your drawers, but they are messy, and you’re not sure which one it’s in.

The probability that the problem set is in drawer k is dk. If drawer k has the problem set and you search there, you have probability pk of finding it. There are a total of m drawers.

Suppose you search drawer i and do not find the problem set.

(a) Find the probability that the paper is in drawer j, where j≠i.

(b) Find the probability that the paper is in drawer i.

Solution: Let Ak be the event that the problem set is in drawer k, and Bk be the event that you find the problem set in drawer k.

| (a) We’ll express the desired probability as P(Aj | Bic). Since this quantity is difficult to reason about directly, we’ll use Bayes’ rule: |

| P(Aj | Bic)=P(Bic | Aj)P(Aj)P(Bic) |

| The first probability, P(Bic | Aj), expresses the probability of not finding the problem set in drawer i given that it’s in a different drawer j. Since it’s impossible to find the paper in a drawer it isn’t in, this is just 1. |

The second quantity, P(Aj), is given to us in the problem statement as dj.

The third probability, P(Bic)=1−P(Bi), is difficult to reason about directly. But, if we knew whether or not the paper was in the drawer, it would become easier. So, we’ll use total probability:

| P(Bi)=P(Bi | Ai)P(Ai)+P(Bi | Aic)P(Aic)=pidi+0(1−di) |

Putting these terms together, we find that

| P(Aj | Bic)=dj1−pidi |

Alternate method to compute the denominator P(Bic): We could use the law of total probability to decompose P(Bic) depending on which drawer the homework is actually in. We have

| P(Bic)=∑k=1mP(Ak)⏟dkP(Bic | Ak)⏟1 if k≠i,(1−pi) if k=i=∑k=1,k≠imdk+(1−pi)di=∑k=1mdk−pidi=1−pidi. |

(b) Similarly, we’ll use Bayes’ rule:

| P(Ai | Bic)=P(Bic | Ai)P(Ai)P(Bic)=(1−pi)di1−pidi |

Take-Away Lessons:

Defining the sample-space is not always going to help solve the problem. (It’s difficult to precisely define the sample space for this particular problem)

When in doubt of being able to precisely define the sample space, try to define events intelligently, i.e., in a way that you use what you’re given in the problem.

The probability law of a probability model is a function on events, or subsets of the sample space, i.e., one can work with the probability law without knowing precisely what the sample-space (as a set) is.

RELATING CONDITIONING ON EVENTS BACK TO RANDOM VARIABLES PREFACE

the conditional probability distributions for random variables that we saw previously are just a special case of conditioning on events. The next video gets into the conditional probability distribution of a random variable given that an event has occurred, which is a way that combines our use of random variables and of events.

THE PRODUCT RULE FOR RANDOM VARIABLES (COURSE NOTES)

In many real world problems, we aren’t given what the joint distribution of two random variables is although we might be given other information from which we can compute the joint distribution. Often times, we can compute out the joint distribution using what’s called the product rule (often also called the chain rule). This is precisely the random variable version of the product rule for events.

As we saw from before, we were able to derive Bayes’ theorem for events using the product rule for events: P(A∩B)=P(A)P(B∣A). The random variable version of the product rule is derived just like the event version of the product rule, by rearranging the equation for the definition of conditional probability. For two random variables X and Y (that take on values in sets X and Y respectively), the product rule for random variables says that

pX,Y(x,y)=pY(y)pX∣Y(x∣y)for all x∈X,y∈Y such that pY(y)>0.

Interpretation: If we have the probability table for Y, and separately the probability table for X conditioned on Y, then we can come up with the joint probability table (i.e., the joint distribution) of X and Y.

What happens when pY(y)=0? Even though pX∣Y(x∣y) isn’t defined in this case, one can readily show that pX,Y(x,y)=0 when pY(y)=0.

To see this, think about what is happening computationally: Remember how pY(y) is computed from joint probability table pX,Y? In particular, we have pY(y)=∑xpX,Y(x,y), so pY(y) is the sum of either a row or a column in the joint probability table (whether it’s a row or column just depends on how you write out the table and which random variable is along which axis–along rows or columns). So if pY(y)=0, it must mean that the individual elements being summed are 0 (since the numbers we’re summing up are nonnegative).

We can formalize this intuition with a proof:

Claim: Suppose that random variables X and Y have joint probability table pX,Y and take on values in sets X and Y respectively. Suppose that for a specific choice of y∈Y, we have pY(y)=0. Then

pX,Y(x,y)=0for all x∈X.

Proof: Let y∈Y satisfy pY(y)=0. Recall that we relate marginal distribution pY to joint distribution pX,Y via marginalization:

0=pY(y)=∑x∈XpX,Y(x,y).

Next, we use a crucial mathematical observation: If a sum of nonnegative numbers (such as probabilities) equals 0, then each of the numbers being summed up must also be 0 (otherwise, the sum would be positive!). Hence, it must be that each number being added up in the right-hand side sum is 0, i.e.,

pX,Y(x,y)=0for all x∈X.

This completes the proof. ◻

Thus, in general:

pX,Y(x,y)={pY(y)pX∣Y(x∣y)if pY(y)>0,0if pY(y)=0. Important convention for this course: For notational convenience, throughout this course, we will often just write pX,Y(x,y)=pY(y)pX∣Y(x∣y) with the understanding that if pY(y)=0, even though pX∣Y(x∣y) is not actually defined, pX,Y(x,y) just evaluates to 0 anyways.

The product rule is symmetric: We can use the definition of conditional probability with X and Y swapped, and rearranging factors, we get:

pX,Y(x,y)=pX(x)pY∣X(y∣x)for all x∈X,y∈Y such that pX(x)>0,

and so similarly we could show that

pX,Y(x,y)={pX(x)pY∣X(y∣x)if pX(x)>0,0if pX(x)=0. Again for notational convenience, we’ll typically just write pX,Y(x,y)=pX(x)pY∣X(y∣x) with the understanding that the expression is 0 when pX(x)=0.

Interpretation: If we’re given the probability table for X and, separately, the probability table for Y conditioned on X, then we can come up with the joint probability table for X and Y.

Importantly, for any two jointly distributed random variables X and Y, the product rule is always true, without making any further assumptions! Also, as a recurring theme that we’ll see later on as well, we are decomposing the joint distribution into the product of factors (in this case, the product of two factors).

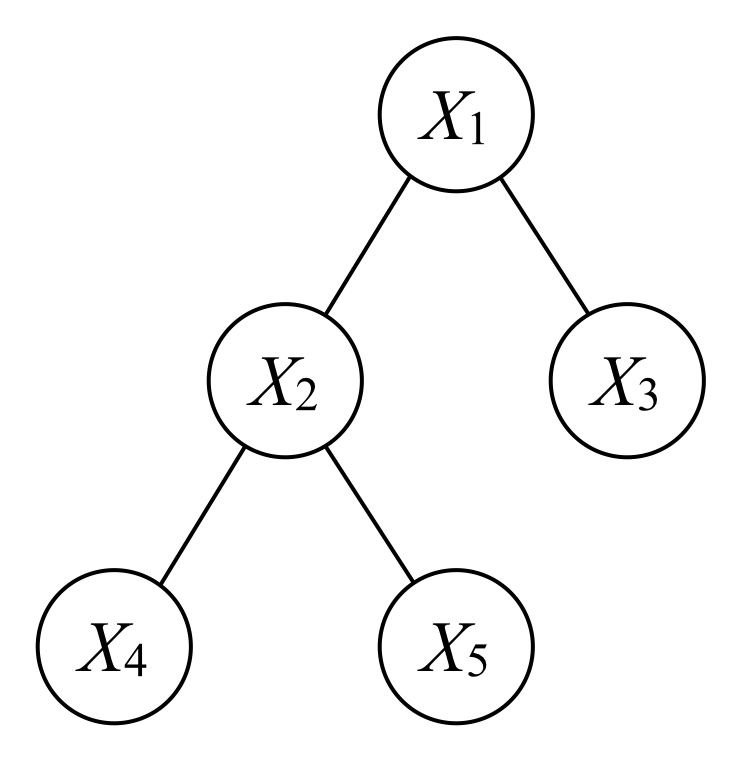

Many random variables: If we have many random variables, say, X1, X2, up to XN where N is not a random variable but is a fixed constant, then we have

Again, we write this to mean that this holds for every possible choice of x1,x2,…,xN for which we never condition on a zero probability event. Note that the above factorization always holds without additional assumptions on the distribution of X1,X2,…,XN.

Note that the product rule could be applied in arbitrary orderings. In the above factorization, you could think of it as introducing random variable X1 first, and then X2, and then X3, etc. Each time we introduce another random variable, we have to condition on all the random variables that have already been introduced.

Since there are N random variables, there are N! different orderings in which we can write out the product rule. For example, we can think of introducing the last random variable XN first and then going backwards until we introduce X1 at the end. This yields the, also correct, factorization

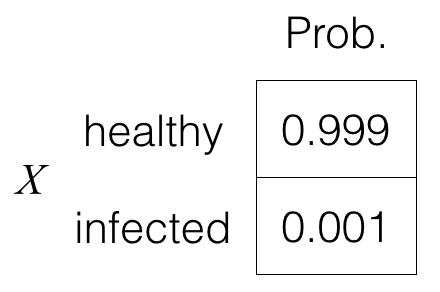

Exercise: The Product Rule for Random Variables - Medical Diagnosis Revisited

Let’s revisit the medical diagnosis problem we saw earlier. We now use random variables to construct a joint probability table.

Let random variable X represent the patient’s condition — whether “healthy” or “infected”, with the following distribution for X:

Meanwhile, the test outcome Y for whether the patient is infected is either “positive” (for the disease) or “negative”. As before, the test is 99% accurate, which means that the conditional probability table for Y given X is as follows (note that we also show how to write things out as a single table):

Bayes’ Rule for Random Variables (Also Called Bayes’ Theorem for Random Variables

BAYES’ THEOREM FOR RANDOM VARIABLES (COURSE NOTES)

In inference, what we want to reason about is some unknown random variable X, where we get to observe some other random variable Y, and we have some model for how X and Y relate. Specifically, suppose that we have some “prior” distribution pX for X; this prior distribution encodes what we believe to be likely or unlikely values that X takes on, before we actually have any observations. We also suppose we have a “likelihood” distribution pY∣X.

After observing that Y takes on a specific value y, our “belief” of what X given Y=y is now given by what’s called the “posterior” distribution pX∣Y(⋅∣y). Put another way, we keep track of a probability distribution that tells us how plausible we think different values X can take on are. When we observe data Y that can help us reason about X, we proceed to either upweight or downweight how plausible we think different values X can take on are, making sure that we end up with a probability distribution giving us our updated belief of what X can be.

Thus, once we have observed Y=y, our belief of what X is changes from the prior pX to the posterior pX∣Y(⋅∣y).

Bayes’ theorem (also called Bayes’ rule or Bayes’ law) for random variables explicitly tells us how to compute the posterior distribution pX∣Y(⋅∣y), i.e., how to weight each possible value that random variable X can take on, once we’ve observed Y=y. Bayes’ theorem is the main workhorse of numerous inference algorithms and will show up many times throughout the course.

Bayes’ theorem: Suppose that y is a value that random variable Y can take on, and pY(y)>0. Then

pX∣Y(x∣y)=pX(x)pY∣X(y∣x)∑x′pX(x′)pY∣X(y∣x′)

for all values x that random variable X can take on.

Important: Remember that pY∣X(⋅∣x) could be undefined but this isn’t an issue since this happens precisely when pX(x)=0, and we know that pX,Y(x,y)=0 (for every y) whenever pX(x)=0.

Proof: We have

pX∣Y(x∣y)=(a)pX,Y(x,y)pY(y)=(b)pX(x)pY∣X(y∣x)pY(y)=(c)pX(x)pY∣X(y∣x)∑x′pX,Y(x′,y)=(d)pX(x)pY∣X(y∣x)∑x′pX(x′)pY∣X(y∣x′),

where step (a) uses the definition of conditional probability (this step requires pY(y)>0), step (b) uses the product rule (recall that for notational convenience we’re not separately writing out the case when pX(x)=0), step (c) uses the formula for marginalization, and step (d) uses the product rule (again, for notational convenience, we’re not separately writing out the case when pX(x′)=0). ◻

BAYES’ THEOREM FOR RANDOM VARIABLES: A COMPUTATIONAL VIEW

Computationally, Bayes’ theorem can be thought of as a two-step procedure. Once we have observed Y=y:

- For each value x that random variable X can take on, initially we believed that X=x with a score of pX(x), which could be thought of as how plausible we thought ahead of time that X=x. However now that we have observed Y=y, we weight the score pX(x) by a factor pY∣X(y∣x), so

new belief for how plausible X=x is:α(x∣y)≜pX(x)pY∣X(y∣x), (2.4)

where we have defined a new table α(⋅∣y) which is not a probability table, since when we put in the weights, the new beliefs are no longer guaranteed to sum to 1 (i.e., ∑xα(x∣y) might not equal 1)! α(⋅∣y) is an unnormalized posterior distribution!

Also, if pX(x) is already 0, then as we already mentioned a few times, pY∣X(y∣x) is undefined, but this case isn’t a problem: no weighting is needed since an impossible outcome stays impossible.

To make things concrete, here is an example from the medical diagnosis problem where we observe Y=positive:

- We fix the fact that the unnormalized posterior table α(⋅∣y) isn’t guaranteed to sum to 1 by renormalizing:

pX∣Y(x∣y)=α(x∣y)∑x′α(x′∣y)=pX(x)pY∣X(y∣x)∑x′pX(x′)pY∣X(y∣x′).

An important note: Some times we won’t actually care about doing this second renormalization step because we will only be interested in what value that X takes on is more plausible relative to others; while we could always do the renormalization, if we just want to see which value of x yields the highest entry in the unnormalized table α(⋅∣y), we could find this value of x without renormalizing!

MAXIMUM A POSTERIORI (MAP) ESTIMATION

| For a hidden random variable X that we are inferring, and given observation Y=y, we have been talking about computing the posterior distribution pX∣Y(⋅ | y) using Bayes’ rule. The posterior is a distribution for what we are inferring. Often times, we want to report which particular value of X actually achieves the highest posterior probability, i.e., the most probable value x that X can take on given that we have observed Y=y. |

The value that X can take on that maximizes the posterior distribution is called the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimate of X given Y=y. We denote the MAP estimate by x^MAP(y), where we make it clear that it depends on what the observed y is. Mathematically, we write

| x^MAP(y)=argmaxxpX∣Y(x | y). |

Note that if we didn’t include the “arg” before the “max”, then we would just be finding the highest posterior probability rather than which value–or “argument”–x actually achieves the highest posterior probability.

In general, there could be ties, i.e., multiple values that X can take on are able to achieve the best possible posterior probability.

Exercise: Bernoulli and Binomial Random Variables

a Bernoulli random variable is like a biased coin flip where probability of heads is . In particular, a Bernoulli random variables is 1 with probability , and 0 with probability . If a random variable has this particular distribution, then we write , where “” can be read as “is distributed as” or “has distribution”. Some people like to abbreviate by writing , , or even just

.

A Binomial random variable can be thought of as independent coin flips, each with probability of heads. For a random variable that has this Binomial distribution with parameters and , we denote it as , read as “ is distributed as Binomial with parameters and “. Some people might also abbreviate and instead of writing , they write or .

(a) True or false: If Y∼Binomial(1,p), then Y is a Bernoulli random variable.

Solution: The answer is true. When there’s only a single flip, counting the number if heads yields precisely the Bernoulli distribution. In particular, we have Y∼Bernoulli(p).

(b) Let’s say we have a coin that turns up heads with probability 0.6. We flip this coin 10 times. What is the probability of seeing the sequence HTHTTTTTHH, where H denotes heads and T denotes tails (so we have heads in the first toss, tails in the second, heads in the third, etc)? (Please be precise with at least 3 decimal places, unless of course the answer doesn’t need that many decimal places. You could also put a fraction.)

By independence, the sequence HTHTTTTTHH has probability

0.6×0.4×0.6×0.4×0.4×0.4×0.4×0.4×0.6×0.6=0.64×0.46.

Note that in general, if there were instead n coin flips where heads appears with probability p, then we would have pnumber of heads(1−p)n−number of heads.

(c) In the previous part, there were 4 heads and 6 tails. Did the ordering of them matter? In other words, would your answer to the previous part be the same if, for example, instead we saw the sequence HHHHTTTTTT (or any other permutation of 4 heads and 6 tails)?

Solution: As our solution to part (b) shows, the ordering of heads/tails does not matter.

(d) From the previous two parts, what we were analyzing was the same as the random variable S∼Binomial(10,0.6). Note that S=4 refers to the event that we see exactly 4 heads. Note that HTHTTTTTHH and HHHHTTTTTT are different outcomes of the underlying experiment of coin flipping. How many ways are there to see 4 heads in 10 tosses?

Solution: The number of ways to see 4 heads in 10 tosses is precisely the number of ways to choose 4 items out of 10, given by the choose operator: ${10 \choose 4} = \frac{10!}{4! 6!} = \boxed {210}$.

In general, the number of ways to see s heads in n tosses is (ns).

(e) Using your answers to parts (b) through (d), what is the probability that S=4?

Solution: There are (104)=210 ways to get 4 heads out of 10, and each way is equally likely with probability given by 0.64×0.46, so summing up the probabilities across all these ways, we have 210×0.64×0.46.

In general, for random variable S∼Binomial(n,p), the probability that S=s for s∈{0,1,…,n} is given by

It might not be a priori obvious why this probability table’s entries should sum to 1.

To show this result, we can use the Binomial Theorem, which says that for any two numbers x and y, and any nonnegative integer n,

Plugging in x=p and y=1−p, we see that the right-hand side directly corresponds to summing across all the entries of probability table pS, and the left-hand side is (p+(1−p))n=1n=1.

Exercise: The Soda Machine

A soda machine advertises 7 different flavors of soda. However, there is only one button for buying soda, which dispenses a flavor of the machine’s choosing. Adam buys 14 sodas today, and notices that they are all either grape or root beer flavored.

(a) Assuming that the soda machine actually dispenses each of its 7 flavors randomly, with equal probability, and independently each time, what is the probability that all 14 of Adam’s sodas are either grape or root beer flavored?

Solution: Let’s first consider a single soda, which could be one of 7 flavors, 2 of which are desired. Thus the probability of the soda being either grape or root beer is 27. Since each soda is dispensed independently, the probability of all 14 sodas being grape or root beer is (27)14≈2.416×10−8.

(b) How would your answer to the (a) change if the machine were out of diet cola, ginger ale, so it randomly chooses one of only 5 flavors?

Solution: If there are only 5 flavors of soda available, the probability of getting either grape or root beer is 25. Thus, once again assuming each soda is chosen independently, the probability that all 14 sodas are grape or root beer is (25)14≈2.684×10−6.

(c) What if the machine only had 3 flavors: grape, root beer, and cherry?

Solution: Similarly, with only 3 flavors to choose from, the probability becomes (23)14≈0.003425.

Independent Random Variables

Exercise: Independent Random Variables

In this exercise, we look at how to check if two random variables are independent in Python. Please make sure that you can follow the math for what’s going on and be able to do this by hand as well.

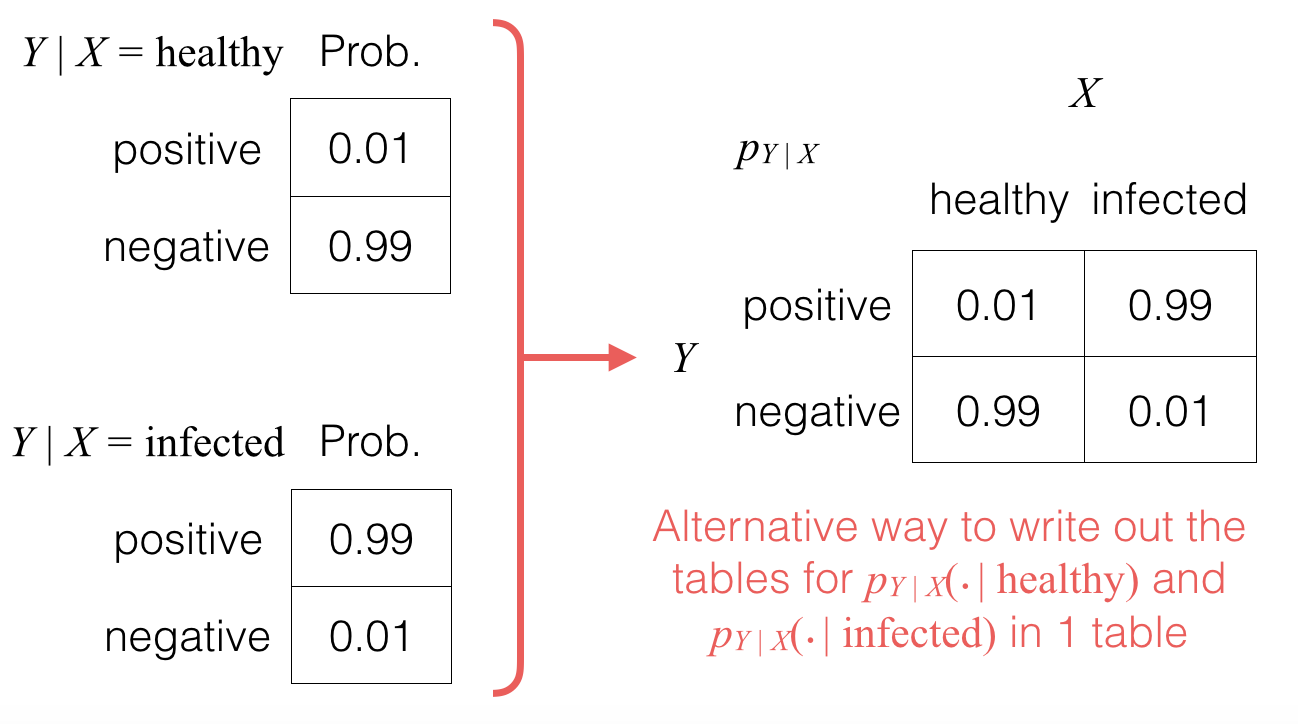

Consider random variables W, I, X, and Y, where we have shown the joint probability tables pW,I and pX,Y.

In Python:

prob_W_I = np.array([[1/2, 0], [0, 1/6], [0, 1/3]])

Note that here, we are not explicitly storing the labels, but we’ll keep track of them in our heads. The labels for the rows (in order of row index): sunny, rainy, snowy. The labels for the columns (in order of column index): 1, 0.

We can get the marginal distributions pW and pI:

prob_W = prob_W_I.sum(axis=1) prob_I = prob_W_I.sum(axis=0)

Then if W and I were actually independent, then just from their marginal distributions pW and pI, we would be able to compute the joint distribution with the formula:

If W and I are independent:pW,I(w,i)=pW(w)pI(i)for all w,i.

Note that variables prob_W and prob_I at this point store the probability tables pW and pI as 1D NumPy arrays, for which NumPy does not store whether each of these should be represented as a row or as a column.

We could however ask NumPy to treat them as column vectors, and in particular, taking the outer product of prob_W and prob_I yields what the joint distribution would be if W and I were independent:

The left-hand side is an outer product, and the right-hand side is precisely the joint probability table that would result if W and I were independent.

To compute and print the right-hand side, we do:

print(np.outer(prob_W, prob_I)) Are W and I independent (compare the joint probability table we would get if they were independent with their actual joint probability table)?

Are W and I independent (compare the joint probability table we would get if they were independent with their actual joint probability table)?

Solution: The answer is No. When you run the code above, you should see that the joint probability distribution for W and I is different from the joint probability of W and I if they were independent. In fact, if they were independent, you’d end up with the joint probability table for X and Y.

Introduction to Decision Making and Expectations

We now know the basics of working with probabilities. But how do we incorporate probabilities into making decisions?

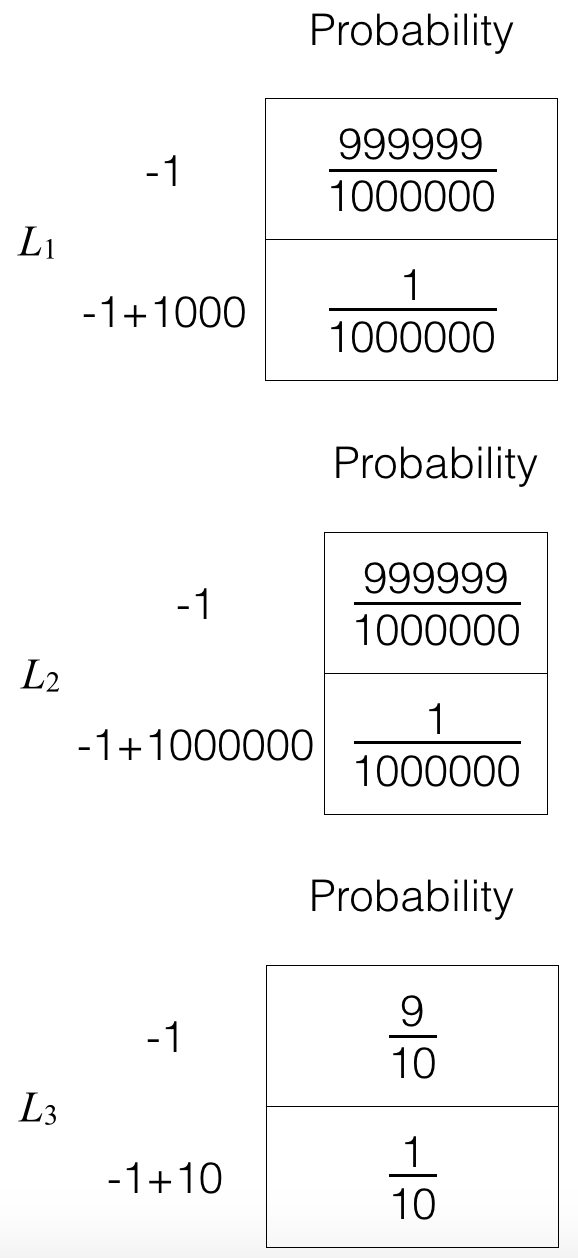

Let’s make this concrete. Suppose we are given the option of playing one of the following lotteries. Which one should we play?

Lottery 1: Pay $1 and have a one in one million chance of winning $1000.

Lottery 2: Pay $1 and have a one in one million chance of winning $1000000.

Lottery 3: Pay $1 and have a one in ten chance of winning $10.

Of course, there isn’t a right or wrong answer here, but what we would like to do is come up with some quantitative way to make a decision. Especially if we want to make decisions automatically based on huge amount of observations, a principled quantitative approach is crucial!

One way to go about making a decision is to compute as score for each of the possible choices and choose the decision with the highest score. In this case of choosing between the three lotteries, for each of the lotteries, we could compute some kind of “average” amount of winnings, accounting for the cost to play.

For example, if we play the first lottery, we definitely lose $1, and then there is a 11000000 chance that we win $1,000. So one way we could write out an “average” amount of winnings is something like

−1+1000⋅11000000=−1+0.001=−0.999.

For now, multiplying the $1,000 by 11000000 can be thought of as a heuristic that signifies that we aren’t guaranteed to win $1,000, and how much we multiply by we’re just picking to be the probability of winning right now.

Using the above way we have just come up with for computing “average” winnings, the second lottery has average winnings

−1+11000000(1000000)=−1+1=0.

That’s not so bad right? The chance of winning is still really low but the average winnings according to this calculation is 0, so it seems like we stand nothing to lose right?

Well, it depends on how much uncertainty we’re willing to tolerate. A one in a million chance seems really low so almost always we would just lose a dollar if we play lottery #2.

In the third lottery, the average winnings is

−1+110(10)=0,

the same as for lottery #2. Sure, we aren’t going to win $1000000 in this game but the chance of winning is way higher: 1/10 instead of 1/1000000. Somehow that should matter right?

On the basis of the average winnings calculation we have done though, lotteries #2 and #3 would be equally good as they give the same highest average winnings of $0.

We now discuss how to quantitatively and rigorously reason about scenarios like the ones we’ve just sketched. The main tool we now introduce is what’s called the expected value of a random variable. In making decisions that account for randomness, it often makes sense to account for an “average” scenario that we should expect. Expectation is about taking an average, accounting for how likely different outcomes are.

In 6.008.1x, after we cover our story here on expected values, we won’t be seeing them again until the third part of the course on learning probabilistic models. The idea there is that what probabilistic model makes sense for your data can be thought of as decision making! We are deciding which model to use instead of, in our example here, deciding which lottery to play!

THE EXPECTED VALUE OF A RANDOM VARIABLE PREFACE

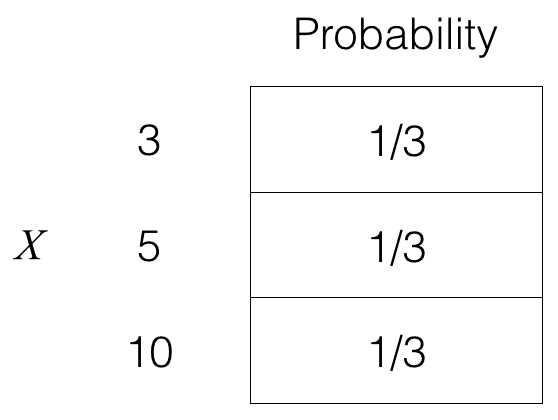

Consider, for example, the mean of three values: 3, 5, and 10. It can be computed as follows:

3+5+103=3⋅13+5⋅13+10⋅13=6.

Notice, on the right-hand side, that we are adding 3, 5, and 10 each weighted by 13. Concretely, consider a random variable X given by the probability table below:

Then the “expected value” of X is given by

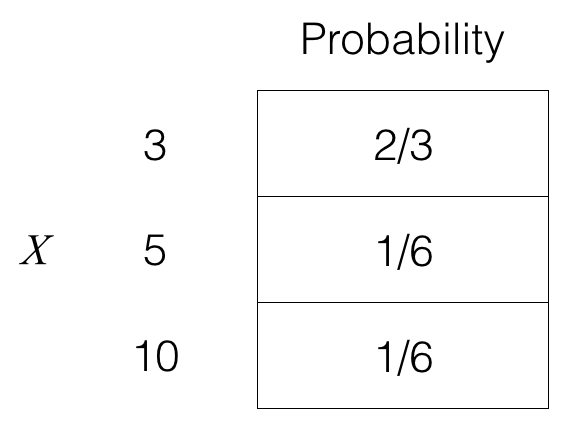

But what if, for instance, we think that 3 is actually much more plausible than 5 or 10? Then what we could do is have the weight on 3 be higher than 13 while decreasing the weights for 5 and 10. Consider if instead we had:

Then the expected value of X is given by

3⋅pX(3)+5⋅pX(5)+10⋅pX(10)=3⋅23+5⋅16+10⋅16=92.

Using probability, we now formalize the concept of expected value of a random variable. As you can see, all we are doing is taking the sum of the labels in the probability table, where we weight each label by the probability of the label. Importantly, the labels are numbers so that it’s clear what adding them means!

Now, for the formal definition:

Definition of expected value: Consider a real-valued random variable X that takes on values in a set X. Then the expected value of X, denoted as E[X], is

E[X]≜∑x∈Xx⋅pX(x).

Having the random variable be real-valued makes it so that we can add up the labels with weights!

Also, note that whereas X can be represented as a probability table, its expectation E[X] is just a single number. The expected value is the sum of the values in the set X, weighted by the probabilities of each of the values. The mean is simply the expected value when all of the values in the set X when there is a uniform probability of each of the values.

Notice that how we came up with the expectation of a random variable X just relied on the probability table for X.

In fact, if we took a different probability table, if the labels are numbers, then we can still compute the expectation! Two important examples are below.

Conditional Expectation

As a first example, suppose we have two random variables X and Y where we know (or we have already computed) pX∣Y(⋅∣y) for some fixed value y, and X is real-valued. Then we can readily compute the expectation for this probability table by multiplying each value x in the alphabet of random variable X by pX∣Y(x∣y) and summing these up to get a weighted average. This yields what is called the conditional expectation of X given Y=y, denoted as

E[X∣Y=y]=∑x∈Xx⋅pX∣Y(x∣y).

Expectation of the Function of a Random Variable

As another example, suppose we have a (possibly not real-valued) random variable X with probability table pX, and we have a function f such that f(x) is real-valued for all x in the alphabet X of X. Then f(X) has a probability table where the labels are all numbers, and so we can compute E[f(X)].

Let’s work out the math here. First, let’s determine the probability table for f(X). To make the notation here easier to parse, let random variable Z=f(X). Note that Z has alphabet Z={f(x):x∈X}. Then the probability table for f(X) can be written as pZ. In terms of the probability table, to compute pZ(z), we first look at every label in table pX that gets mapped to z, i.e., the set {x∈X:f(x)=z}. Then we sum up the probabilities of these labels to get the probability that Z=z, i.e., pZ(z)=∑x∈X such that f(x)=zpX(x).

We introduce a new piece of notation here called an indicator function 1{⋅} $\mathbf{1}{ \cdot }$ that takes as input a statement S and outputs:

1{S}={1if S happens,0otherwise.

Then the probability that Z=z can be written

pZ(z) = ∑x∈X such that f(x)=zpX(x) = ∑x∈X1{f(x)=z}pX(x).Next, we compute the expectation of Z=f(X):

E[Z] = ∑z∈ZzpZ(z) = ∑z∈Zz[∑x∈X1{f(x)=z}pX(x)] = ∑x∈X∑z∈Zz1{f(x)=z}pX(x)⏟there is only 1 nonzero term here: when z=f(x) = ∑x∈Xf(x)pX(x).Hence, since Z=f(X), we can write

E[f(X)]=∑x∈Xf(x)pX(x).

Variance and Standard Deviation

the important concept of variance, which measures how much a random variable deviates from its expectation. This can be thought of as a measure of uncertainty. Higher variance means more uncertainty.

The variance of a real-valued random variable X is defined as

var(X)≜E[(X−E[X])2].

Note that as we saw previously, E[X] is just a single number. To keep the variance of X, what you could do is first compute the expectation of X.

Some times, people prefer keeping the units the same as the original units (i.e., without squaring), which you can get by computing what’s called the standard deviation of a real-valued random variable X:

std(X)≜var(X).

Note that when we first introduced the three lotteries and computed average winnings, we didn’t account for the uncertainty in the average winnings. Here, it’s clear that the third lottery has far smaller standard deviation and variance than the second lottery.

As a remark, often in financial applications (e.g., choosing a portfolio of stocks to invest in), accounting for uncertainty is extremely important. For example, you may want to maximize profit while ensuring that the amount of uncertainty is not too high as to not be reckless in investing.

In the case of the three lotteries, to decide between them, you could for example use a score that is of the form

E[Li]−λ⋅std(Li)for i=1,2,3,

where λ≥0 is some parameter that you choose for how much you want to penalize uncertainty in the lottery outcome. Then you could choose the lottery with the highest score.

Can variance be negative?

Solution: The answer is no. Variance cannot be negative since it is taking the (weighted) average of a bunch of squared quantities. A real number squared is always nonnegative. The weighted average of nonnegative numbers is also nonnegative.

For random variables X and Y for which we know (or have computed) the conditional distribution pX∣Y(⋅∣y), and for any function f such that f(x) is a real number for every x in the alphabet of X, then

E[f(X)∣Y=y]=∑xf(x)pX∣Y(x∣y).

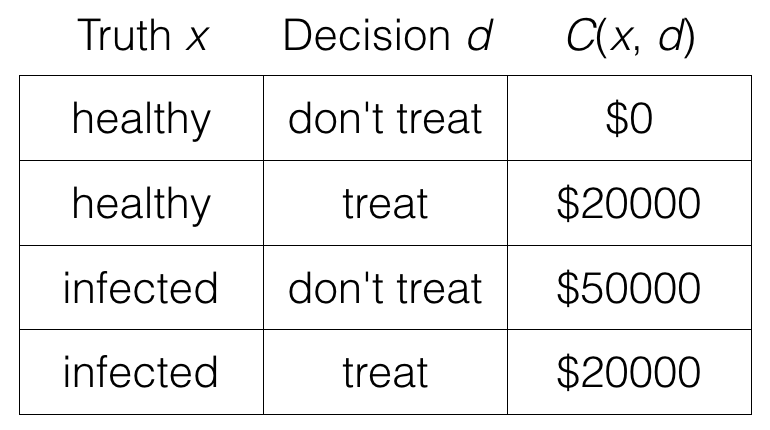

We previously computed the probability that someone has a infection given that a test for the infection turned out positive. But how do we translate this into a decision of whether or not we should treat the person? Ideally, we should always choose to treat people who, in truth, have the infection and choose “don’t treat” for people without the infection. However, it is possible that we may treat actually healthy people, a false positive that leads to unnecessary medical costs. As well, we may fail to treat people with the infection, a false negative that could require more expensive treatment later on.

We can encode these costs into the following “cost table” (or cost function) C(⋅,⋅), where C(x,d) is the cost when the patient’s true infection state is x (“healthy” or “infected”), and we make decision d (“treat” or “don’t treat”). For our problem, here is the cost function:

Putting together the pieces, the decision rule that achieves the lowest cost can be written as:

Expectations of Multiple Random Variables

How does expected value work when we have many random variables? In this exercise, we look at some specific cases that draw out some important properties involving expected values.

Let’s look at when there are two random variables X and Y with alphabets X and Y respectively. Then how expectation is defined for multiple random variables is as follows: For any function f:X×Y→R,

E[f(X,Y)]=∑x∈X,y∈Yf(x,y)pX,Y(x,y).

(Note that “∑x∈X,y∈Y” can also be written as “∑x∈X∑y∈Y”.)

For example:

E[X+Y]=∑x∈X,y∈Y(x+y)pX,Y(x,y).

Let’s look at some properties of the expected value of the sum of multiple random variables.

First, as a warm-up, show that:

E[X+Y]=E[X]+E[Y].

This equality is called linearity of expectation and it holds regardless of whether X and Y are independent.

We previously saw that a binomial random variable with parameters n and p can be thought of as how many heads there are in n tosses where the probability of heads is p.

A different way to view a binomial random variable is that it is the sum of n i.i.d. Bernoulli random variables each of parameter p. As a reminder, a Bernoulli random variable is 1 with probability p and 0 otherwise. Suppose that X1,X2,…,Xn are i.i.d. Bernoulli(p) random variables, and S=∑i=1nXi.

p*(1-p)2 + (1-p)*(0-p)2

Wow this so helpful Derek!

In all my studies of statistics I’ve never heard anything on how linearity can bypass and bypass independence!

So going by this example:

number of times for which a King in the deck is followed by another King

Indicator for the event that the ith card is a King with another King following it

So I make the following assumptions:

Since I’m designating as an indicator variable then:

= because of non replacement and the 52nd card cannot have king after it so $P{R_{52}=1} = 0$.

Part 1: Probability and Inference > Week 4: Decisions and Expectations > Practice Problem: The Law of Total Expectation

THE LAW OF TOTAL EXPECTATION

For a set of events B1,…,Bn that partition the sample space Ω (so the Bi’s don’t overlap and together they fully cover the full space of possible outcomes)

A similar statement is true for the expected value of a random variable, called the law of total expectation: for a random variable X (with alphabet X) and a partition B1,…,Bn of the sample space,

where

Solution: There are different ways to prove the law of total expectation. We take a fairly direct approach here, first writing everything in terms of outcomes in the sample space.

The main technical hurdle is that the events B1,…,Bn are specified directly in the sample space, whereas working with values that X takes on requires mapping from the sample space to the alphabet of X.

We will derive the law of total expectation starting from the right-hand side of the equation above, i.e., ∑i=1nE[X∣Bi]P(Bi).

We first write E[X∣Bi] in terms of a summation over outcomes in Ω:

THE LAW OF TOTAL EXPECTATION (SOLUTION)

Part 1: Probability and Inference > Week 4: Measuring Randomness > Introduction to Information-Theoretic Measures of Randomness

We just saw some basics for decision making under uncertainty and expected values of random variables. One way we saw for measuring uncertainty was variance. Now we look at a different way of measuring uncertainty or randomness using some ideas from information theory.

In this section, we answer the following questions in terms of bits (as in bits on a computer; everything stored on a computer is actually 0’s and 1’s each of which is 1 bit):

How do we measure how random an event is?

How do we measure how random a random variable or a distribution is?

How do we measure how different two distributions are?

How much information do two random variables share?

For now, this material may seem like a bizarre exercise relating to expectation of random variables, but as we will see in the third part of the course on learning probabilistic models, information theory provides perhaps the cleanest derivations for some of the learning algorithms we will derive!

More broadly but beyond the scope of 6.008.1x, information theory is often used to show what the best possible performance we should even hope an inference algorithm can achieve such as fundamental limits to how accurate we can make a prediction. And if you can show that your inference algorithm’s performance meets the fundamental limit, then that certifies that your inference algorithm is optimal! Inference and information theory are heavily intertwined!

Part 1: Probability and Inference > Week 4: Measuring Randomness > Shannon Information Content

SHANNON INFORMATION CONTENT: MEASURING RANDOMNESS IN AN EVENT (COURSE NOTES)

First, let’s consider storing an integer that isn’t random. Let’s say we have an integer that is from 0,1,…,63. Then the number of bits needed to store this integer is log2(64)=6 bits: you tell me 6 bits and I can tell you exactly what the integer is.

A different way to think about this result is that we don’t a priori know which of the 64 outcomes is going to be stored, and so each outcome is equally likely with probability 164. Then the number of bits needed to store an event A is given by what’s called the “Shannon information content” (also called self-information):

log21P(A).

In particular, for an integer x∈{0,1,…,63}, the Shannon information content of observing x is

log21P(integer is x)=log211/64=log264=6 bits.

If instead, the integer was deterministically 0 and never equal to any of the other values 1,2,…,63, then the Shannon information content of observing integer 0 is

log21P(integer is 0)=log211=0 bits.

This is not surprising in that a outcome that we deterministically always observe tells us no new information. Meanwhile, for each integer x∈{1,2,…,63},

log21P(integer is x)=log210=∞ bits.

How could observing one of the integers {1,2,…,63} tell us infinite bits of information?! Well, this isn’t an issue since the event that we observe any of these integers has probability 0 and is thus impossible. An interpration of Shannon information content is how surprised we would be to observe an event. In this sense, observing an impossible event would be infinitely surprising.

It is possible to have the Shannon information content of an event be some fractional number of bits (e.g., 0.7 bits). The interpretation is that from many repeats of the underlying experiment, the average number of bits needed to store the event is given by the Shannon information content, which can be fractional.

the sum we’re computing is a telescoping sum where all the terms cancel out except for the first one: log2128=7.

In general, if we guess right after k tries, then the total amount of information “learned” is:

Put another way, 7 bits of information are needed before you know the number, and with wrong guesses, you learn very few bits of information (although as the number of possibilities shrinks, wrong guesses provide more and more bits of information).

Part 1: Probability and Inference > Week 4: Measuring Randomness > Shannon Entropy

SHANNON ENTROPY: MEASURING RANDOMNESS IN A DISTRIBUTION/RANDOM VARIABLE (COURSE NOTES

To go from the number of bits contained in an event to the number of bits contained in a random variable, we simply take the expectation of the Shannon information content across the possible outcomes. The resulting quantity is called the entropy of a random variable:

H(X)=∑xpX(x)log21pX(x)⏟Shannon information content of event X=x.

The interpretation is that on average, the number of bits needed to encode each i.i.d. sample of a random variable X is H(X). In fact, if we sample n times i.i.d. from pX, then two fundamental results in information theory that are beyond the scope of this course state that: (a) there’s an algorithm that is able to store these n samples in nH(X) bits, and (b) we can’t possibly store the sequence in fewer than nH(X) bits!

Example: If X is a fair coin toss “heads” or “tails” each with probability 1/2, then

H(X)=pX(heads)log21pX(heads)+pX(tails)log21pX(tails)=12⋅log2112⏟1+12⋅log2112⏟1=1 bit.

Example: If X is a biased coin toss where heads occurs with probability 1 then

H(X)=pX(heads)log21pX(heads)+pX(tails)log21pX(tails)=1⋅log211⏟0+0⋅⋅log210⏟1=0 bits,

where 0log210=0log21−0log20=0 using the convention that 0log20≜0. (Note: You can use l’Hopital’s rule from calculus to show that limx→0xlogx=0 and limx→0xlog1x=0.)

Notation: Note that entropy H(X)=∑xpX(x)log21pX(x) $H(X) = \sum _ x p_ X(x) \log 2 \frac{1}{p X(x)}$ is in the form of an expectation! So in fact, we can write an expectation:

H(X)=E[log21pX(X)].

Entropy gives a very different measure for uncertainty than variance, which we saw previously. Whereas variance var(X)=E[(X−E[X])2] measures how far a random variable is expected to deviate from its expected value E[X], entropy measures how many bits are needed on average to store each i.i.d. sample of a random variable X.

In computing the entropy of a random variable X, we look at the probabilities in the probability table of X. Did we have to look at the labels in the probability table (i.e., the labels correspond to the alphabet X of X)?

Solution: The answer is no. You can see this in the Python code: we don’t need to look at the alphabet X.

Suppose for a random variable X, we take its probability table and shuffle the ordering of the probabilities (but otherwise keep the labels the same). For example, if X is a biased coin flip with probability of heads 3/4, suppose we took its table and instead have the probability of tails be 3/4 and the probability of heads be 1/4.

By shuffling the ordering of the probabilities, does the entropy of the random variable change?

Solution: The answer is no. Since what the labels are does not actually matter (of course, we cannot have the same label appear twice in the table though), we can permute the labels (or the probabilities) and get the same entropy.

We’ve seen an example where the entropy is 0 bits. Can entropy be negative? (While there is an intuitive answer for this, see if you can show it mathematically.)

Solution: The answer is no. First, note that for any probability p∈[0,1], the Shannon information content corresponding to this probability is log2(1/p), which has a value from 0 to infinity, i.e., Shannon information content is always nonnegative. Shannon entropy is just a weighted average of Shannon information content, where the weights are nonnegative. A nonnegative weighted sum of a collection of nonnegative numbers remains nonnegative.

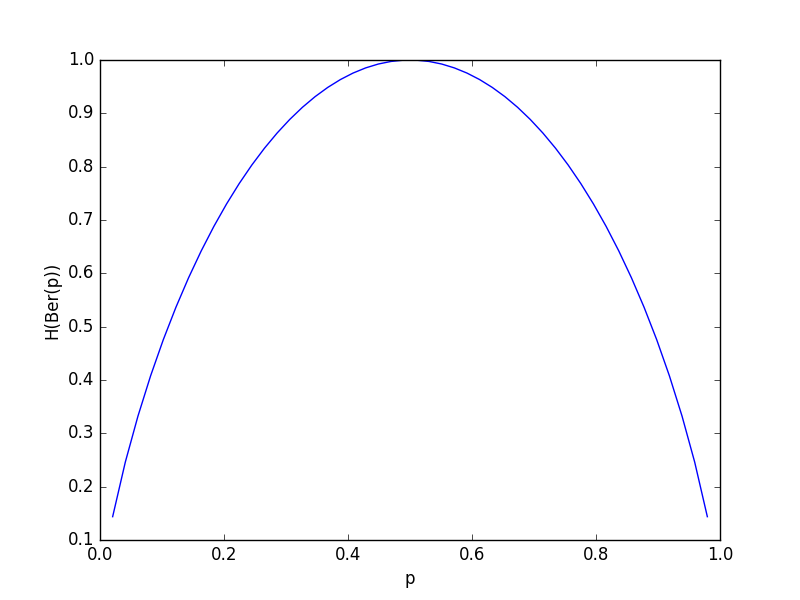

For a random variable X that takes on one of two values, one with probability p and the other with probability 1−p, plot the entropy H(p) as a function of p in Python. For what value of p is the entropy maximized (i.e., what value of p yields the largest H(X))? Please provide an exact answer.

Note that to get a list of values of p evenly spaced from 0 to 1 with for example 50 steps between them, you can use the NumPy linspace function:

p_list = np.linspace(0, 1, 50) Solution: Here’s the code to plot:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

p_list = np.linspace(0, 1, 50)

plt.figure()

plt.plot(p_list,

[entropy(np.array([p, 1-p])) for p in p_list])

plt.xlabel('p')

plt.ylabel('H(Ber(p))')

plt.show()

Note that for the y-axis label, we called it H(Ber(p)) since the distribution we are looking at is Bernoulli with parameter p (remember that a Bernoulli is like a coin flip and takes on value 1 with probability p and 0 otherwise).

The maximum occurs at p=1/2, which corresponds to a uniform distribution on the two possible values, meaning that every possible value is equally likely. This is like a fair coin flip for which we really can’t predict whether it’s going to be heads or tails (whereas, for example, if the probability of heads were 0.6, then if we always predicted heads, then we would be correct more than 50-50 chance).

As we’ll see shortly, for any distribution with alphabet size k, a uniform distribution that assigns equal probability 1/k to all k outcomes achieves the largest possible entropy (out of all distributions with alphabet size k).

INFORMATION DIVERGENCE: MEASURING HOW DIFFERENT TWO DISTRIBUTIONS ARE (COURSE NOTES)

Information divergence (also called “Kullback-Leibler divergence” or “KL divergence” for short, or also “relative entropy”) is a measure of how different two distributions p and q (over the same alphabet) are. To come up with information divergence, first, note that entropy of a random variable with distribution p could be thought of as the expected number of bits needed to encode a sample from p using the information content according to distribution p:

∑xp(x)⏟expectation using plog21p(x)⏟information content according to p≜EX∼p[log21p(X)].

Here, we have introduced a new notation: EX∼p means that we are taking the expectation with respect to random variable X drawn from the distribution p. If it’s clear which random variable we are taking the expectation with respect to, we will often just abbreviate the notation and write Ep instead of EX∼p.

If instead we look at the information content according to a different distribution q, we get

∑xp(x)⏟expectation using plog21q(x)⏟information content according to q≜EX∼p[log21q(X)].

It turns out that if we are actually sampling from p but encoding samples as if they were from a different distribution q, then we always need to use more bits! This isn’t terribly surprising in light of the fundamental result we alluded to that entropy of a random variable with distribution p is the minimum number of bits needed to encode samples from p.

Information divergence is the price you pay in bits for trying to encode a sample from p using information content according to q instead of according to p:

D(p∥q)=EX∼p[log21q(X)]−EX∼p[log21p(X)].

Information divergence is always at least 0, and when it is equal to 0, then this means that p and q are the same distribution (i.e., p(x)=q(x) for all x). This property is called Gibbs’ inequality.

Gibbs’ inequality makes information divergence seem a bit like a distance. However, information divergence is not like a distance in that it is not symmetric: in general, D(p∥q)≠D(q∥p).

Often times, the equation for information divergence is written more concisely as

D(p∥q)=∑xp(x)logp(x)q(x),

which you can get as follows:

D(p∥q)=EX∼p[log21q(X)]−EX∼p[log21p(X)]=∑xp(x)log21q(x)−∑xp(x)log21p(x)=∑xp(x)[log21q(x)−log21p(x)]=∑xp(x)log2p(x)q(x).

Example: Suppose p is the distribution for a fair coin flip:

p(x)={12if x=heads,12if x=tails. Meanwhile, suppose q is a distribution for a biased coin that always comes up heads (perhaps it’s double-headed):

q(x)={1if x=heads,0if x=tails. Then

D(p∥q)=p(heads)log2p(heads)q(heads)+p(tails)log2p(tails)q(tails)=12log2121+12log2120⏟∞=∞ bits.

This is not surprising: If we are sampling from p (for which we could get tails) but trying to encode the sample using q (which cannot possibly encode tails), then if we get tails, we are stuck: we can’t store it! This incurs a penalty of infinity bits.

Meanwhile,

D(q∥p)=q(heads)log2q(heads)p(heads)+q(tails)log2q(tails)p(tails)=1log2112+0log2012⏟0=1 bit.

When we sample from q, we always get heads. In fact, as we saw previously, the entropy of the distribution for an always-heads coin flip is 0 bits since there’s no randomness. But here we are sampling from q and storing the sample using distribution p. For a fair coin flip, encoding using distribution p would store each sample using on average 1 bit. Thus, even though a sample from q is deterministically heads, we store it using 1 bit. This is the penalty we pay for storing a sample from q using distribution p.

Notice that in this example, D(p∥q)≠D(q∥p). They aren’t even close — one is infinity and the other is finite!

Part 1: Probability and Inference > Week 4: Measuring Randomness > Exercise: Information Divergence

We now look at a different way to think of Shannon entropy for a random variable X with alphabet X.

Let random variable U have what’s called a uniform distribution over alphabet X, meaning that

| pU(x)=1 | X | for all x∈X. |

Notationally, we can write U∼Uniform(X).

| In the following problems, suppose the number of labels in X is given by k, i.e., k= | X | . |

What is H(U) in terms of k?

Next, we examine the divergence between pX and the uniform distribution. Show that D(pX∥pU) can be written of the form

D(pX∥pU)=f(k)−H(X),

for a function f that you will determine:

What is f? Please write your answer in all lowercase with no spaces, and use “log” to mean log base 2 (please do not try to write a subscript 2). Note that we’re just asking for what f is, so if your answer is, for instance, exp, then just put exp and not exp(k).

In particular, f is log base 2, which for this part you answer by just saying log to mean log base 2.