Python

What are those three lines between def a(x): and return x + 1? These lines are called the docstring of the function. A docstring is a special type of comment that is used to document what your function is doing. Typically, docstrings will explain what the function expects the type(s) of the argument(s) to be, and what the function is returning. In Python, docstrings appear immediately after the def line of a function, before the body. Docstrings start and end with triple quotes - this can be triple single quotes or triple double quotes, it doesn’t matter as long as they match. To sum up this general form:

Week 4: Good Programming Practices > 7. Testing and Debugging

Black-box testing is a method of software testing that tests the functionality of an application. Recall from the lecture that a way to think about black-box testing is to look at both:

The possible paths through the specification.

The possible boundary cases.

Undoubtably many - if not all - of the listed tests look like they would be pretty good for testing the function size. However, we want you to think critically about the way size is specified - including possible boundary cases - and pick a set of tests that adequately and fully tests all paths and boundary conditions. Be sure the set of tests you pick does not have extraneous, useless, or repetitive tests.

A good black box test suite would contain tests for the following conditions: Empty set, Set of size 1, and Set of size greater than 1.

Black-box testing is a method of software testing that tests the functionality of an application. Recall from the lecture that a way to think about black-box testing is to look at both the paths through the specification and the possible boundary cases. In this example, the boundary cases all have to do with the size of aSet. Specifically these boundary cases are when aSet contains zero, one, or many items.

The remaining conditions would not further test the functionality of the size function because an odd, even, or prime sized set are all sets of size greater than 1. Nothing in the function specification suggests there is anything special or unique about odd, even, or prime sized sets, so testing those cases specifically simply repeats the test “Set of size greater than 1”.

a path-complete glass box test suite would find test cases that go through every possible path in the code. This is different from black-box testing, because in black-box testing you only have the function specification. For glass-box testing, you actually know how the function you are testing is defined. Thus you can use this definition to figure out how many different paths through the code exist, and then pick a test suite based on that knowledge.

Undoubtably many - if not all - of the listed tests look like they would be pretty good for testing the function maxOfThree. However, we want you to think critically about the way maxOfThree is defined - including possible boundary cases - and pick a set of tests that adequetly and fully tests all paths and boundary conditions. A good first step will be to look at the function definition and figure out what paths through the code exist. Then, look through the suggested test suites one test at a time and see if the suite tests every single path.

def maxOfThree(a,b,c) :

"""

a, b, and c are numbers

returns: the maximum of a, b, and c

"""

if a > b:

bigger = a

else:

bigger = b

if c > bigger:

bigger = c

return bigger

a path-complete glass box test suite would find test cases that go through every possible path in the code. In this case, that means finding all possibilities for the conditional tests a > b and c > bigger. So, we end up with four possible paths that correspond to Test Suite A:

Case 1: a > b and c > bigger - this corresponds to test maxOfThree(2, -10, 100).

Case 2: a > b and c <= bigger - this corresponds to test maxOfThree(6, 1, 5)

Case 3: a <= b and c > bigger - this corresponds to test maxOfThree(7, 9, 10).

Case 4: a <= b and c <= bigger - this corresponds to test maxOfThree(0, 40, 20)

Test Suite B seems to explicitly test each of a, b, and c being the max of the three numbers, but this does not go through all possible paths in the code.

Test Suite C seems to be a good sampling of the space of input numbers, but it does not go through all possible paths in the code.

def union(set1, set2):

"""

set1 and set2 are collections of objects, each of which might be empty.

Each set has no duplicates within itself, but there may be objects that

are in both sets. Objects are assumed to be of the same type.

This function returns one set containing all elements from

both input sets, but with no duplicates.

"""

if len(set1) == 0:

return set2

elif set1[0] in set2:

return union(set1[1:], set2)

else:

return set1[0] + union(set1[1:], set2)

A good glass box test suite would try to test a good sample of all the possible paths through the code. So, it should contain tests that test when set1 is empty, when set1[0] is in set2, and when set1[0] is not in set2. The test suite should also test when the recursion depth is 0, 1, and greater than 1.

Remember that glass box testing is a method of software testing that tests the internal structures and workings of a piece of code. When we look at the code for union, we see a set of conditionals that ask about set1. Thus a good glass box test suite will contain tests that match the following lines from the conditional statements in the code:

len(set1) == 0 - matched by the test union('', 'abc')

set1[0] in set2 - matched by the test union('a', 'abc')

set1[0] not in set2 (this is the else: of the conditional) - matched by the test union('d', 'abc')

In addition, because union is a recursive function, we should make sure our test set considers a recursion depth of 0, 1, and many. In this case, recursion depth is covered by some of the tests we’ve already chosen:

Recursion depth = 0 - matched by the test union('', 'abc')

Recursion depth = 1 - matched by the tests union('a', 'abc'), union('d', 'abc')

Recursion depth > 1 - matched by the test union('ab', 'abc')

Note that this test suite is NOT path complete because it would take essentially infinite time to test all possible recursive depths.

Let’s examine now why the other test suites weren’t as good as Test Suite D:

Test Suite A looks at a good sampling of set sizes for set1 and set2, but does not explore the if-else paths in the code. set1 never contains any element in set2.

Test Suite B does not explore the paths in the code because it never varies the contents of set1.

Test Suite C does not contain a test that explores the path when set1 has an element that is not in set2.

In glass box testing, we try to sample as many paths through the code as we can. In the case of loops, we want to sample three general cases:

Not executing the loop at all.

Executing the loop exactly once.

Executing the loop multiple times.

Test Suite B has cases that explores all three loop cases.

Test Suite A only explores paths that execute the loop 0 or 1 times.

Test Suite C only explores paths that execute the loop more than 1 time.

###

raise Exception(“0”) just lets you raise your own generic exception titled “0”. If you ever did this in real code it would probably be something like “Exception(“Invalid input”) or something more helpful.

The except Exception as ex: just gives you a name for the exception, so you can print it out on the next line:

try: raise Exception(“Test exception”) except Exception as ex: print(ex)

When the above code runs, it will raise the generic exception with a title “Test exception”, then in the except block, it will catch that exception and print out the title:

Output:

Test exception

Using something like “except Exception as ex” just gives you a name (ex) for the exception that you can then use to print it out, or log it somewhere.

def fancy_divide(list_of_numbers, index): try: try: denom = list_of_numbers[index] for i in range(len(list_of_numbers)): list_of_numbers[i] /= denom finally: raise Exception(“0”) except Exception as ex: print(ex)

Since it is just the general Exception type, and not a specific one like ValueError, it will catch most types of exceptions. So it’s useful to give it a name (ex), so you can print it out for example and figure out what the problem is. BTW you can call it anything you want, “ex” is just a convention.

Just so you know, these are pretty convoluted examples, and not really things you see in real code. They are just to challenge you and make sure you understand the mechanics. You would probably never raise your own exception in the finally block, and it’s generally bad practice to catch the general Exception, as you should catch specific exceptions like ValueError or ZeroDivisionError based on what you are expecting. Because likely the code to handle those two cases would be different. except blocks are for fixing the problem usually, not just printing out an error message like we often do here.

Here is a more useful example, that tries to get a valid integer from the user, and catches exceptions if they enter some other data:

while True: user_input = input(“Please enter a number: “) try: user_int = int(user_input) except ValueError as ex: print(“That was not an integer, try again”) print(ex) else: break # else block is executed if there was no exception # which means the user properly entered a number, so # we can break the loop

loop is over, so user_int is now valid:

print(“Valid int received:”, user_int)

So that code will keep looping forever, asking the user for input, and trying to turn it into an int. If they enter a letter, or a string, or something like that, it will raise a ValueError exception, which we catch and give them a warning. We also print out the exception. Once they enter a proper integer, the else block is executed, and the break exits the loop.

As Kiwi said, it’s always helpful to play around with it yourself. You can test this code here:

https://repl.it/DocA/1

MIT 6.00.2X

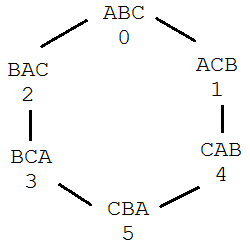

We can label the permutations a through f and construct a graph as such:

a <–> b <–> c <–> d <–> e <–> f <–> a

Clearly, it takes a maximum of 3 movements along edges to get from any node to another. The maximum number of permutations happens when we go from ABC to CBA. We have to go ABC -> BAC -> BCA -> CBA.

In any given permutation, n students are lined up. Since one may only swap the positions of two adjacent students, there are exactly pairs we are able to swap. Each of these swaps will create a distinct ordering, so there are exactly childern of each node.

Given two permutations, what is the maximum number of swaps it will take to reach one from the other? Answer: \(n * (n - 1)/2\)

Consider the case where the two permutations whose exchange would take the maximum number of swaps. Clearly these are two whose orders are opposite. It takes $n-1$

swaps to move the last person in line to the first position. This leaves the rest of the line’s old order intact.

Next it takes $n-2$ swaps to move the last person in line to the second position. We continue until only one more swap is needed (switching the last two people in line). This takes swaps \((n - 1) + (n - 2) + … + 2 + 1 = n * (n - 1)/2\)

Exercise 4

Consider our continuing problem of permutations of three students in a line. Use the enumeration we established when adding the nodes to our graph. That is,

nodes = [] nodes.append(Node(“ABC”)) # nodes[0] nodes.append(Node(“ACB”)) # nodes[1] nodes.append(Node(“BAC”)) # nodes[2] nodes.append(Node(“BCA”)) # nodes[3] nodes.append(Node(“CAB”)) # nodes[4] nodes.append(Node(“CBA”)) # nodes[5]

so that ABC is Node 0, BCA is Node 3, etc.

Using Depth First Search, and beginning at the listed source nodes, give the first path found to the listed destination nodes. For the purpose of this exercise, assume DFS prioritizes lower numbered nodes. For example, if Node 2 is connected to Nodes 3 and 4, the first path checked will be 23. Additionally, DFS will never return to a node already in its path.

To denote a path, simply list the numbers of the nodes exactly as done in the lecture.

Hint: Visual representation

You can never go wrong with drawing a picture of the problem. Here is one possible visualization. The possible permutations are denoted in the graph below. From each node, you can choose to go in either direction. In this particular depth-first-search problem, you will choose the lower numbered node over the higher numbered one, even if it will lead to a longer path from the source to the destination.

We saw before that for permutations of 3 people in line, any two nodes are at most three edges, or four nodes, away. But DFS has yielded paths longer than three edges! In this graph, given a random source and a random destination, what is the probability of DFS finding a path of the shortest possible length?

incorrect

2/3 Loading

Explanation:

First, realize that the structure of this graph is a set of six nodes, all connected in a circle. Each node has two edges that connect it to adjacent nodes.

Given any node, we know that DFS will prioritize the lower-numbered neighbor. Thus, for any destination, we first check for paths along this side. If our destination is our source, we terminate the DFS, and return a path of length zero, which is clearly the shortest. Otherwise, we continue in a circle in one direction. We cannot change direction once we have begun to traverse the circle, as the path may not include any node more than once. It will have found the shortest path for the nodes that are 0, 1, 2, or 3 edges away, but will yield paths of length 4 and 5 for the last two nodes that are, in reality, 2 and 1 edges away, respectively. As it has found the shortest path for 4 nodes, but not for 2, the probability is 4 in 6, or 2/3.

Exercise 6

In the following examples, assume all graphs are undirected. That is, an edge from A to B is the same as an edge from B to A and counts as exactly one edge.

A clique is an unweighted graph where each node connects to all other nodes. We denote the clique with nodes as KN. Answer the following questions in terms of

.

What is the asymptotic worst-case runtime of a Breadth First Search on KN? For simplicity, write

as just n, as n^2, etc.

Answer:

BFS begins by checking all the paths of length 1. In its worst case, it must check the paths to every node from the source to find the destination. This is at most, checks.

Consider a graph of two nodes, A and B, connected by an edge. You wish to search for a path from A to B. As there is exactly one edge in the graph, and exactly one path from A to B, both run in an equal number of steps.

While Shortest Path DFS may find the desired node first in this case, it still must explore all other paths before it has determined which path is the fastest. BFS will explore only a fraction of the paths.

Shortest Path DFS must always explore every path from the source to the destination to ensure that it has found the shortest path. Once BFS has found a path, it knows that it is the shortest, and does not have to explore any other paths.

UNIT 2 > Lecture 5 - Stochastic Thinking > Exercise 1

For the following explanations of different types of programmatic models, fill in the blank with the appropriate model the definition describes.

A __ model is one whose behavior is entirely predictable. Every set of variable states is uniquely determined by parameters in the model and by sets of previous states of these variables. Therefore, these models perform the same way for a given set of initial conditions, and it is possible to predict precisely what will happen.

正确 deterministic A ____ model is one in which randomness is present, and variable states are not described by unique values, but rather by probability distributions. The behavior of this model cannot be entirely predicted.

正确 stochastic A ___ model does not account for the element of time. In this type of model, a simulation will give us a snapshot at a single point in time.

正确 static A ___ model does account for the element of time. This type of model often contains state variables that change over time.

正确 dynamic A ___ model does not take into account the function of time. The state variables change only at a countable number of points in time, abruptly from one state to another.

正确 discrete A __ model does take into account the function of time, typically by modelling a function f(t) and the changes reflected over time intervals. The state variables change in an unbroken way through an infinite number of states.

正确 continuous

UNIT 2 > Lecture 5 - Stochastic Thinking

import random random.randint(1, 5) 4 random.choice([‘apple’, ‘banana’, ‘cat’]) ‘cat’

How would you randomly generate an even number x, 0 <= x < 100? Fill out the definition for the function genEven(). Please generate a uniform distribution over the even numbers between 0 and 100 (not including 100).

There are many good answers to this problem, some easier than others :)

def genEven(): return random.randrange(0, 100, 2)

def genEven(): return random.choice(range(0, 100, 2))

def genEven(): return int(random.random() * 50)*2 # Random float x, 0.0 <= x < 1.0

def genEven(): return random.choice(range(0, 50))*2

def genEven(): x = random.randint(0, 98) while x % 2 != 0: x = random.randint(0, 98) return x

# Possible solutions:

def deterministicNumber(): return 10 # or 12 or 14 or 16 or 18 or 20

Write a deterministic program, deterministicNumber, that returns an even number between 9 and 21.

# or

def deterministicNumber(): random.seed(0) # This will be discussed in the video “Drunken Simulations” return 2 * random.randint(5, 10)

# Possible solutions: def stochasticNumber(): return 2 * random.randint(5, 10)

# or

def stochasticNumber(): return random.randrange(10, 22, 2)

# or, again, something like that.

UNIT 2 > Lecture 5 - Stochastic Thinking > Video: Probabilities

Moral 1: It takes a lot of trials to get a good estimate of the frequency of occurrence of a rare event. We’ll talk lots more in later lectures about how to knowwhen we have enough trials. Moral 2: One should not confuse the sample probabilitywith the actual probability Moral 3: There was really no need to do this by simulation, since there is a perfectly good closed form answer. We will see many examples where this is not true.

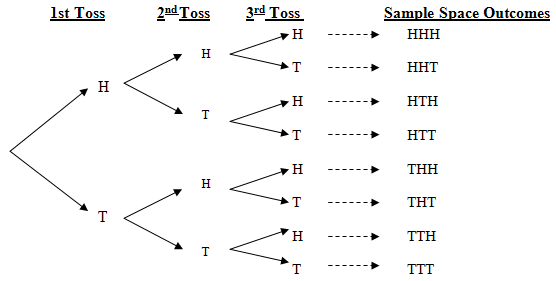

You can answer the following questions in one of two ways - you can calculate the probability directly, or, if you’re having trouble, you can simply write out the entire sample space for the problem. A sample space is defined as a listing of all possible outcomes of a problem, and it can be written in many ways - a tree or a grid are popular options. For example, here is a diagram of the sample space for 3 coin tosses.

Some vocabulary before we begin: an event is a subset of the sample space, or, a collection of possible outcomes. A probability function assigns an event, A, a probability P(A) that represents the likelihood of event A occuring.

As an example, let’s say we flip a coin. Define the event H as the event that the coin comes up heads. We can assign the probability P(H) = 1/2; the likelihood that event H occurs.

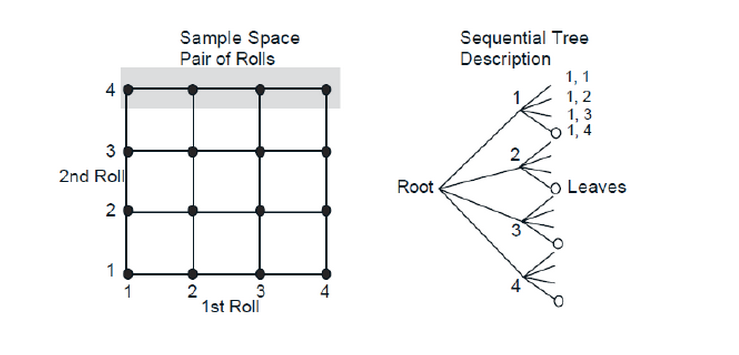

Here is a visual representation of the sample space for 2 rolls of a four sided die. The left represents the 16 outcomes as a 2D grid; the right represents the outcomes as a tree, where each tree path represents one possible outcome.

Each of the 16 outcomes in the sample space has equal probability (1/16) of occuring. So, for all of the above questions, you could simply use the visual representations to count up your answers. However, for large sample spaces this isn’t feasible and it is instead better to be able to calculate the answers directly. So let’s take a look at how to do that.

-

What is the size of the sample space for one roll of a four sided die? 4

-

What is the size of the sample space for two rolls of a four sided die? 4**2 = 16

-

P({sum of the rolls is even}) = 8/16 = 1/2

-

P({rolling a 2 followed by a 3}) = P({2, 3}) = 1/16

-

P({rolling a 2 and a 3}) = P({2, 3}) + P({3, 2}) = 1/16 + 1/16 = 2/16 = 1/8

-

P({sum of the rolls is odd}) = 8/16 = 1/2

-

P({first roll equal to second roll}) = P({both 1}) + P({both 2}) + P({both 3}) + P({both 4}) = 1/16 + 1/16 + 1/16 + 1/16 = 4/16 = 1/4. Another way of thinking about this is that it doesn’t matter what the first roll is, just that the second roll matches it. So, the probability of that event is (4/4) * (1/4) = 1/4: 4/4 for the first roll (we don’t care what it is), times 1/4 chance that the second roll matches the first roll.

-

P({first roll larger than second}) = P({4, <1, 2, 3>}) + P({3, <1, 2>}) + P({2, 1}) = 3/16 + 2/16 + 1/16 = 6/16 = 3/8

-

P({at least one roll equal to 4}) = P({4, <1, 2, 3>}) + P({<1, 2, 3>, 4}) + P({4, 4}) = 3/16 + 3/16 + 1/16= 7/16

-

P({nether roll is equal to 4}) = 1 - P({at least one roll equal to 4}) = 1 - 7/16 = 9/16

In this problem, we’re going to calculate some various probabilities.

Explanation:

What is the size of the sample space for two rolls of a ten sided die? 10**2 = 100

What is the size of the sample space for three rolls of an eight sided die? 8**3 = 512

What is the size of the sample space drawing from a deck of 52 cards? 52

What is the size of the sample space drawing from two decks of 52 cards? 52**2 = 2704

P({rolling a 2 followed by a 3}) = P({2, 3}) = 1/100

P({first roll larger than second roll}) = P({10, <1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9>}) + P({9, <1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8>}) + … + P({2, 1}) = 9/100 + 8/100 + 7/100 + 6/100 + 5/100 + 4/100 + 3/100 + 2/100 + 1/100 = 45/100 = 9/20

P({all three rolls are equal}) = P({all 1}) + P({all 2}) + … + P({all 8}) = 1/512 + 1/512 + 1/512 + 1/512 + 1/512 + 1/512 + 1/512 + 1/512 = 8/512 = 1/64. Another way to think of it: it doesn’t matter what the first roll is, but the second and third rolls must match the first roll. So the probability can be expressed as (8/8) * (1/8) * (1/8) = 1/64.

P({ace of hearts}) = P({one card}) = 1/52

P({drawing a card with suite spades}) = 13/52 = 1/4

P({ace of any suit}) = P({ace of hearts}) + P({ace of clubs}) + P({ace of spaces}) P({ace of diamonds}) = 1/52 + 1/52 + 1/52 + 1/52 = 4/52 = 1/13

P({any card except an ace}) = 1 - P({ace of any suit}) = 1 - 1/13 = 12/13

P({both cards are aces}) = 4/52 * 3/51 = 12/2652 = 1/221. The probability of an ace is 4/52. On the second draw, if an ace was drawn the first time, there are only 3 aces left and only 51 cards remaining. Thus the probability that the second card is also an ace is 3/51.

P({two cards are the same suit}) = This is an interesting problem. There are a few ways of calculating this, but a very simple way is to note that it doesn’t matter what suit the first card is; what matters is that the second card’s suit matches the suit of the first card. If the first card is a spade, there is a 13/52 = 1/4 chance the second card will also be a spade. Following this logic, you’ll find that there’s always a 1/4 chance the second card’s suit will match the first card’s suit, thus P({two cards are the same suit}) = 1/4.

You pick three balls in succession out of a bucket of 3 red balls and 3 green balls. Assume replacement after picking out each ball. What is the probability of each of the following events?

Explanation:

The probability of drawing a red ball is 1/2, so the probability of drawing 3 is (1/2)**3 = 1/8.

P({R, G, R}) = 1/2 * 1/2 * 1/2 = 1/8

P({R, R, G}) + P({R, G, R}) + P({G, R, R}) = 1/8 + 1/8 + 1/8 = 3/8

P({R, R, G}) + P({R, G, R}) + P({G, R, R}) + P({R, R, R}) = 1/8 + 1/8 + 1/8 + 1/8 = 4/8 = 1/2

In this problem, we don’t assume the balls are replaced after being drawn. This changes the probability because with every draw, there is one less ball to pick from. The probability of drawing three red balls is 3/6 * 2/5 * 1/4 – for the first pick, there are three red balls available and six balls total. For the second pick, if we picked a red ball first, there are now two red balls available and five balls total. For the third pick, if both the first and second picks were red balls, there is now one red ball available and four balls total. Multiply together to get P({R, R, R}) = 1/20.

However the problem asked to find the probability of drawing 3 balls of the same color. Thus this probability is P({R, R, R}) + P({G, G, G}). The above analysis works for green balls as well, thus P({R, R, R}) + P({G, G, G}) = 1/20 + 1/20 = 2/20 = 1/10.

UNIT 2 > Lecture 5 - Stochastic Thinking > Video: Random Walks

Simulation Models

A description of computations that provide useful information about the possible behaviors of the system being modeled Descriptive, not prescriptive Only an approximation to reality “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” –George Box

To model systems that are mathematically intractable To extract useful intermediate results Lend themselves to development by successive refinement and “what if” questions

If you were going to use random.seed in a real-life simulation instead of just when you are debugging a simulation, would you want to seed it with 0?

Explanation: No; by using random.seed, you create a deterministic simulation rather than a stochastic simulation. You should never use random.seed in a real-life situation, regardless of the seed value!

Is the following code deterministic or stochastic?

import random

mylist = []

for i in range(random.randint(1, 10)):

random.seed(0)

if random.randint(1, 10) > 3:

number = random.randint(1, 10)

mylist.append(number)

print(mylist)

Explanation:

Answer: Stochastic

This code sample returns a list of 8s. The length of the list is determined by a stochastic variable (the first call to randint). If you are using Canopy, you will notice that the very first time you run the program, the length of the array varies. If you keep clicking the green run button to re-run the program, the length of the array will always be 3. This is because we have set the seed. To completely reset, you will have to restart the kernel via the menu option (Run -> Restart Kernel) or via the keyboard (Ctrl with the period key).

Which of the following alterations (Code Sample A or Code Sample B) would result in a deterministic process?

import random

# Code Sample A

mylist = []

for i in range(random.randint(1, 10)):

random.seed(0)

if random.randint(1, 10) > 3:

number = random.randint(1, 10)

if number not in mylist:

mylist.append(number)

print(mylist)

# Code Sample B

mylist = []

random.seed(0)

for i in range(random.randint(1, 10)):

if random.randint(1, 10) > 3:

number = random.randint(1, 10)

mylist.append(number)

print(mylist)

Check one, none, or both.

Code Sample A Code Sample B 正确 Explanation: Answer: Both! Code Sample A will always return [7]. Code Sample B will always return [1,9,7,8,10,9]. Therefore both of these versions of the original code are deterministic.